Navigate to chronological milestones from 1878 to 2014

Help

1878

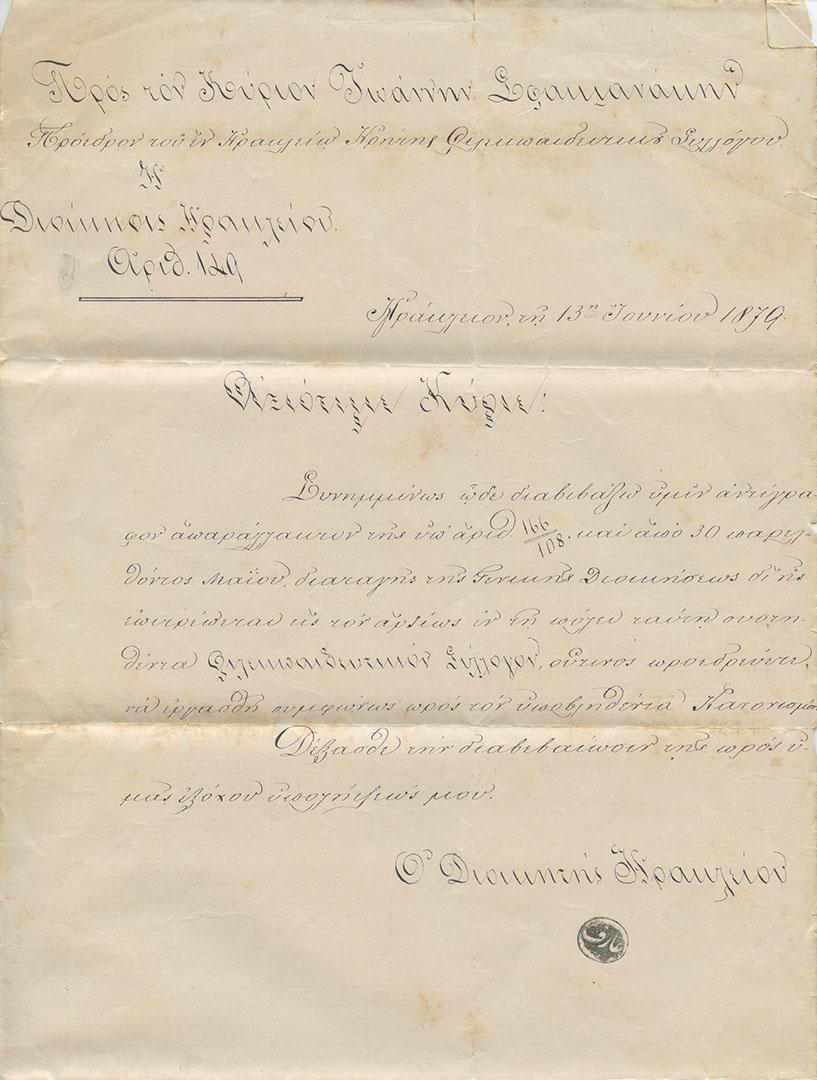

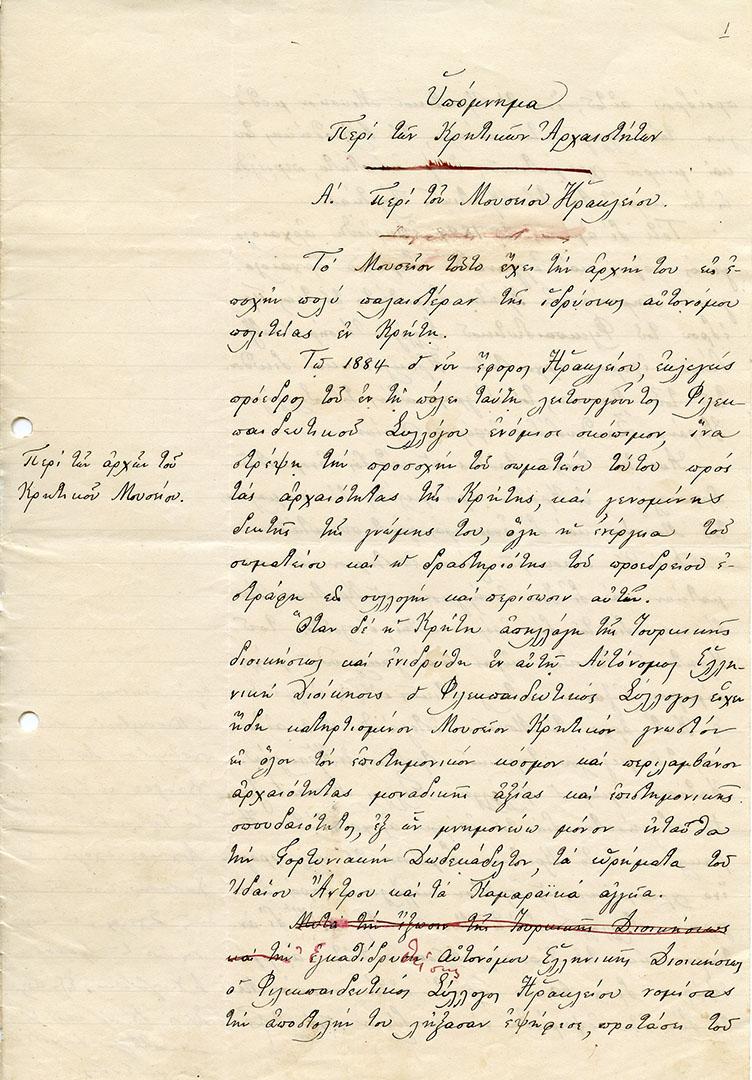

The Educational Society of Heraklion is established. Its activities led to the founding of the Cretan Museum, the nucleus of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

1881

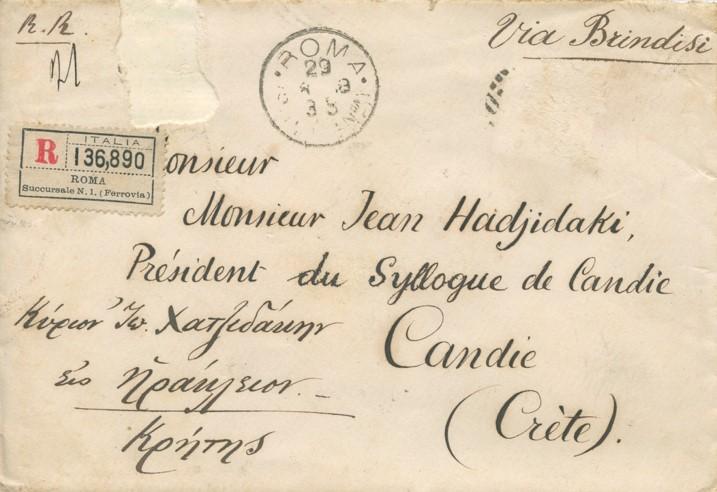

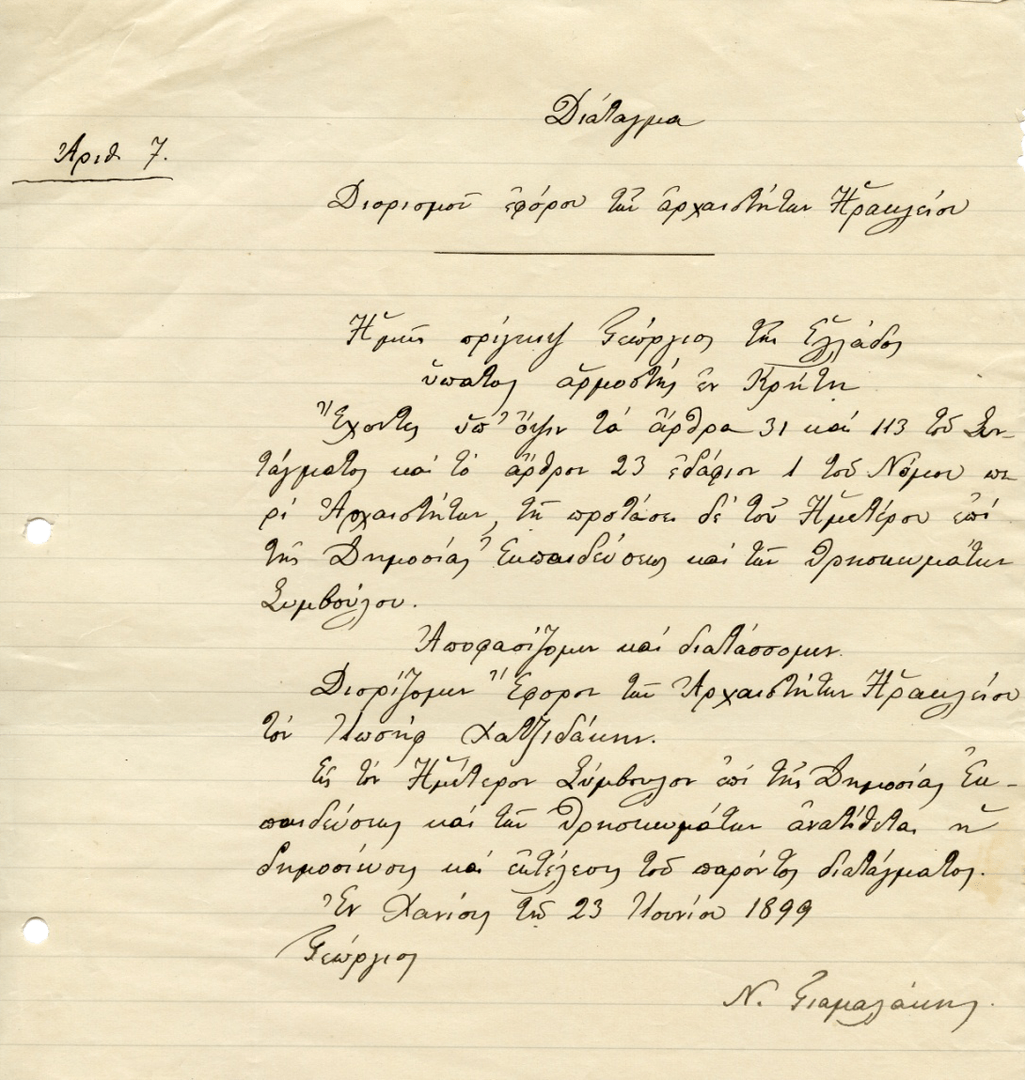

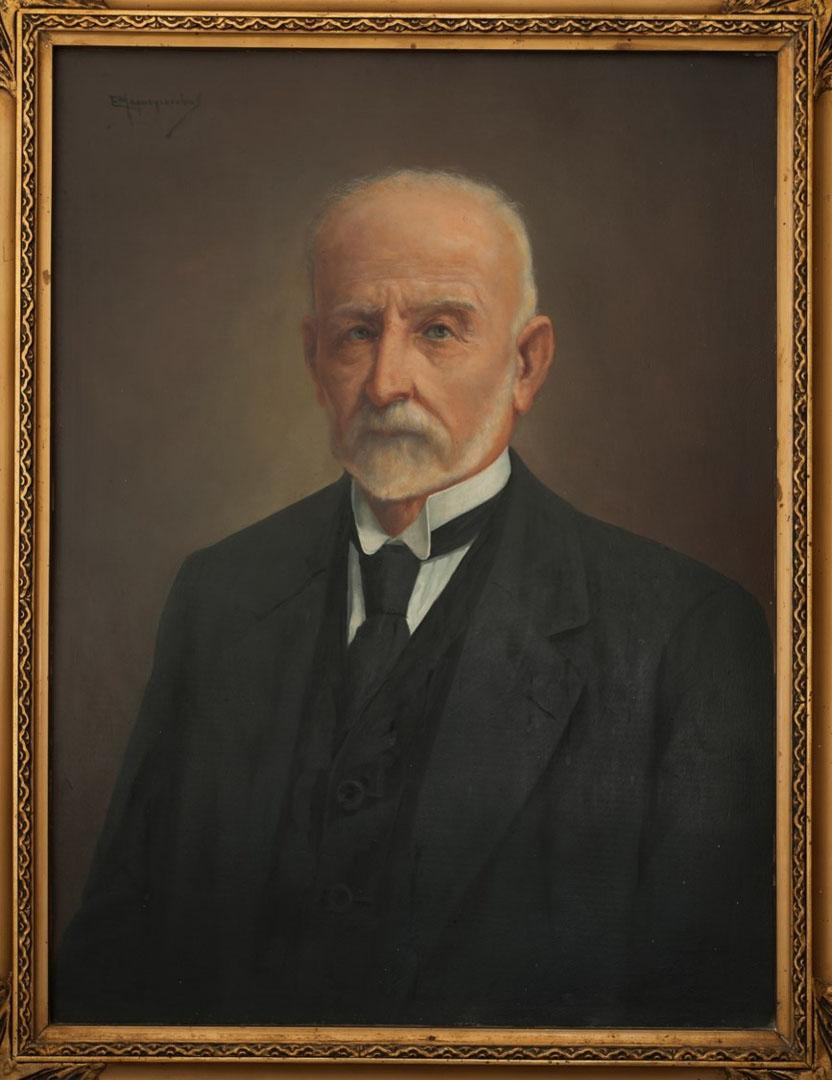

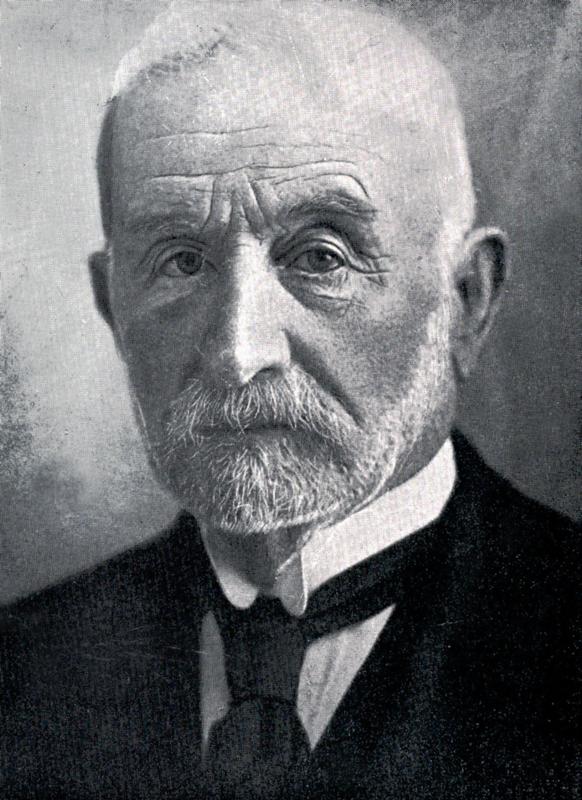

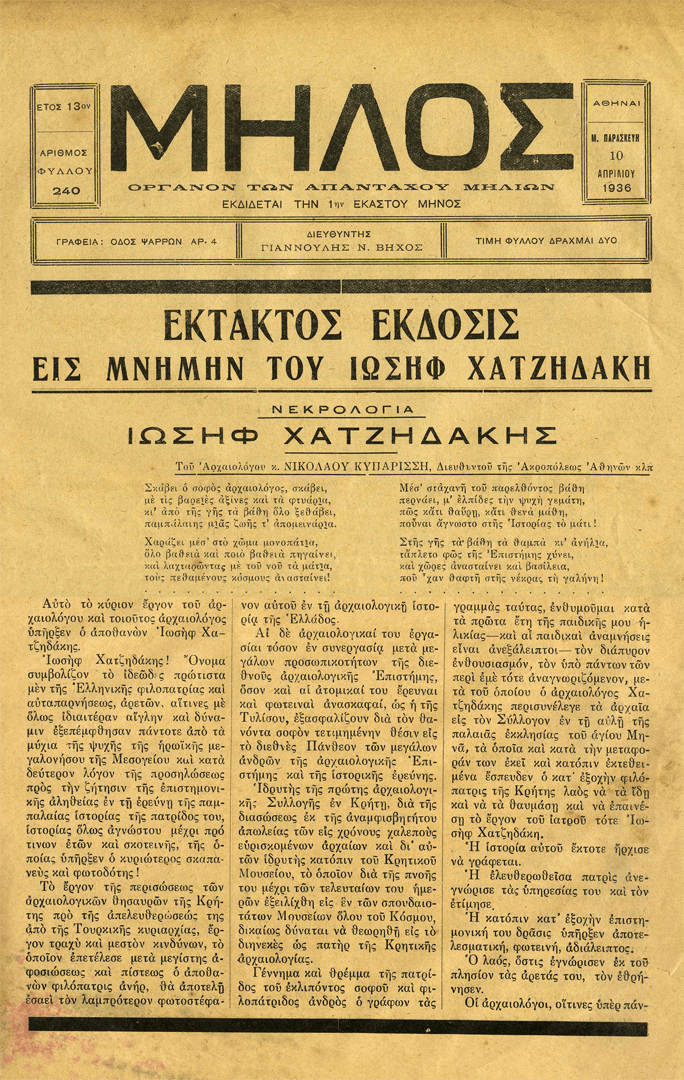

Iosif Hatzidakis (also transliterated Joseph Hazzidakis) (1848-1936), first set foot on Crete, his family’s place of origin, at the age of 33. A gynaecologist-obstetrician and autodidact archaeologist, he played a decisive role in the foundation of the Cretan Museum, becoming its first Director.

1883

Almost immediately after establishing himself in Heraklion, the cosmopolitan I. Hatzidakis was unanimously elected President of the Educational Society of Heraklion, becoming a major figure of Cretan archaeology. He deeply influenced archaeological research in Crete in the late 19th century.

1884

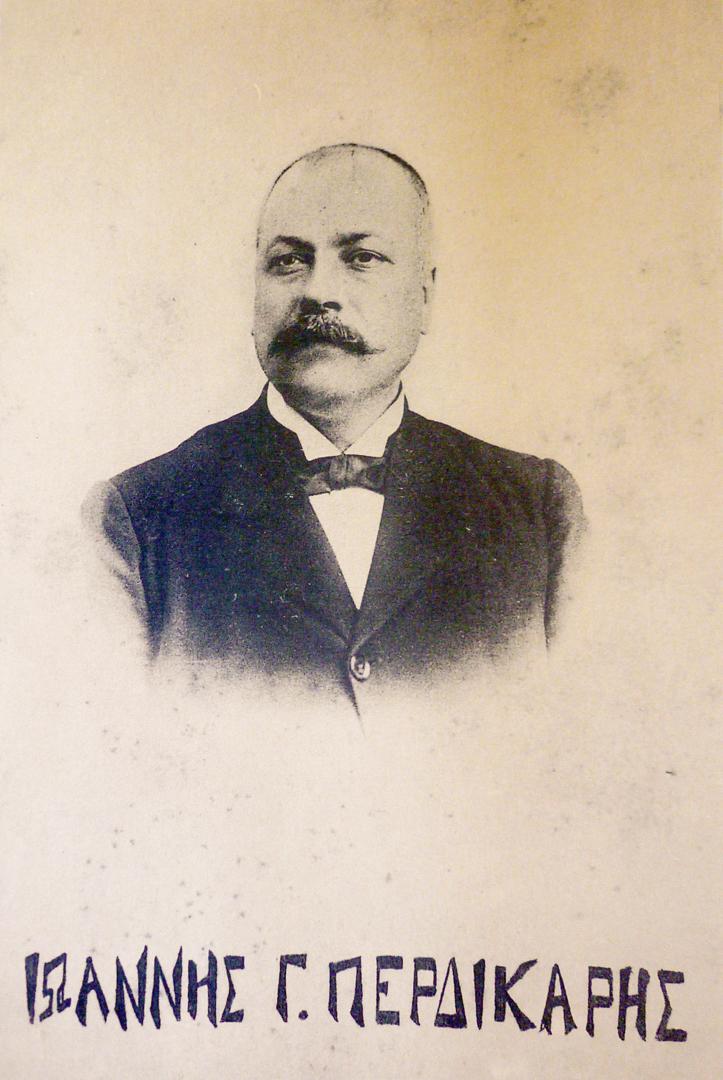

On the initiative of Iosif Hatzidakis and philologist Ioannis Perdikaris, the Educational Society turned its attention to the preservation and study of Cretan antiquities, in what was to be a key decision for the future of the Cretan past.

1885

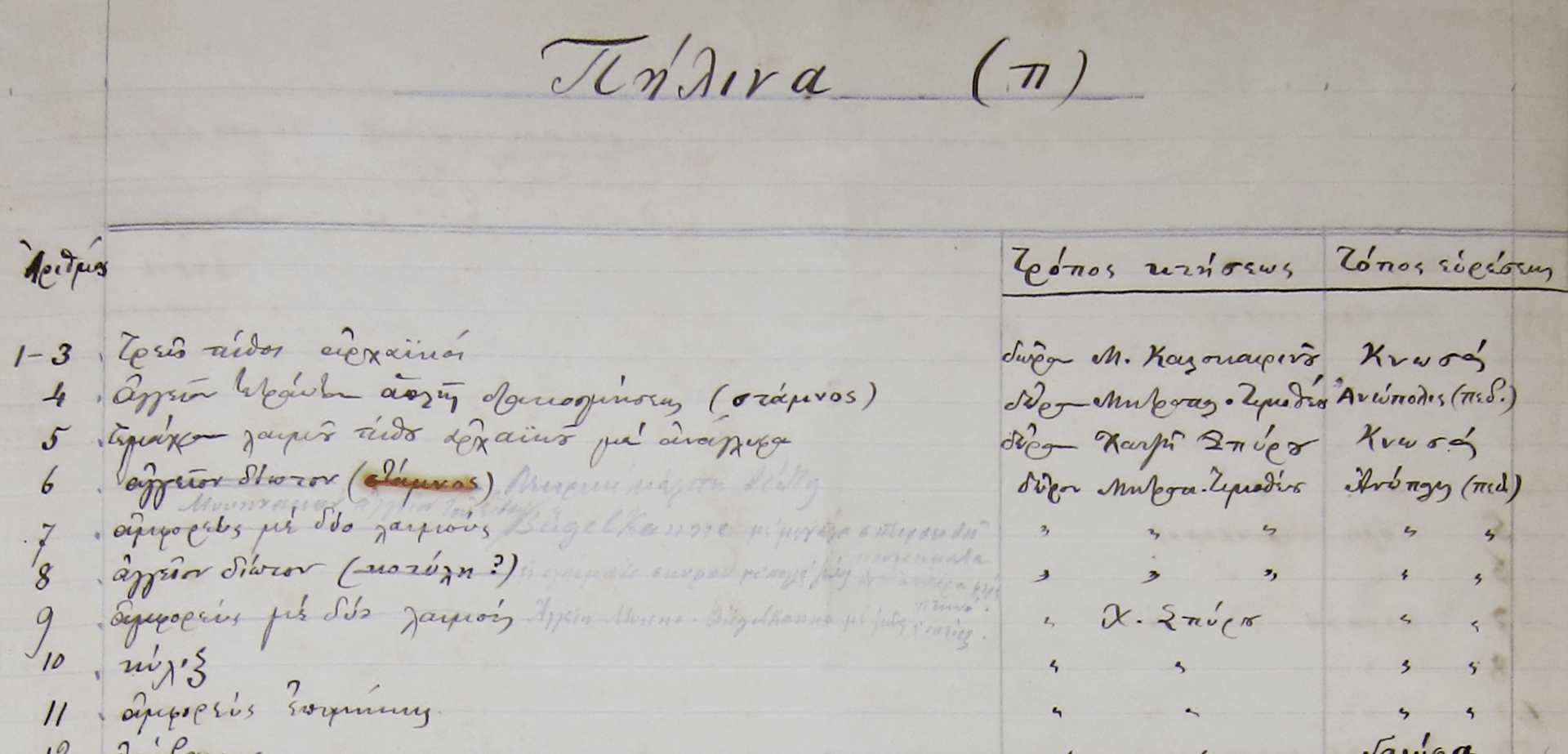

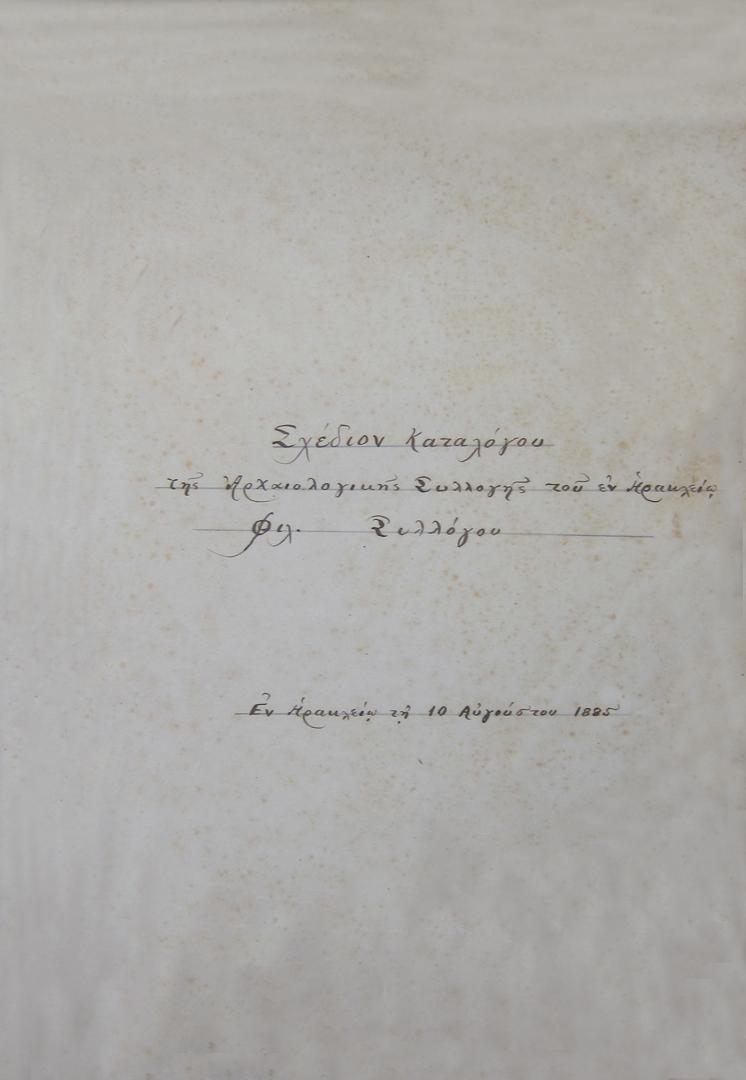

The Educational Society organised and recorded the antiquities it rescued, making them accessible to all.

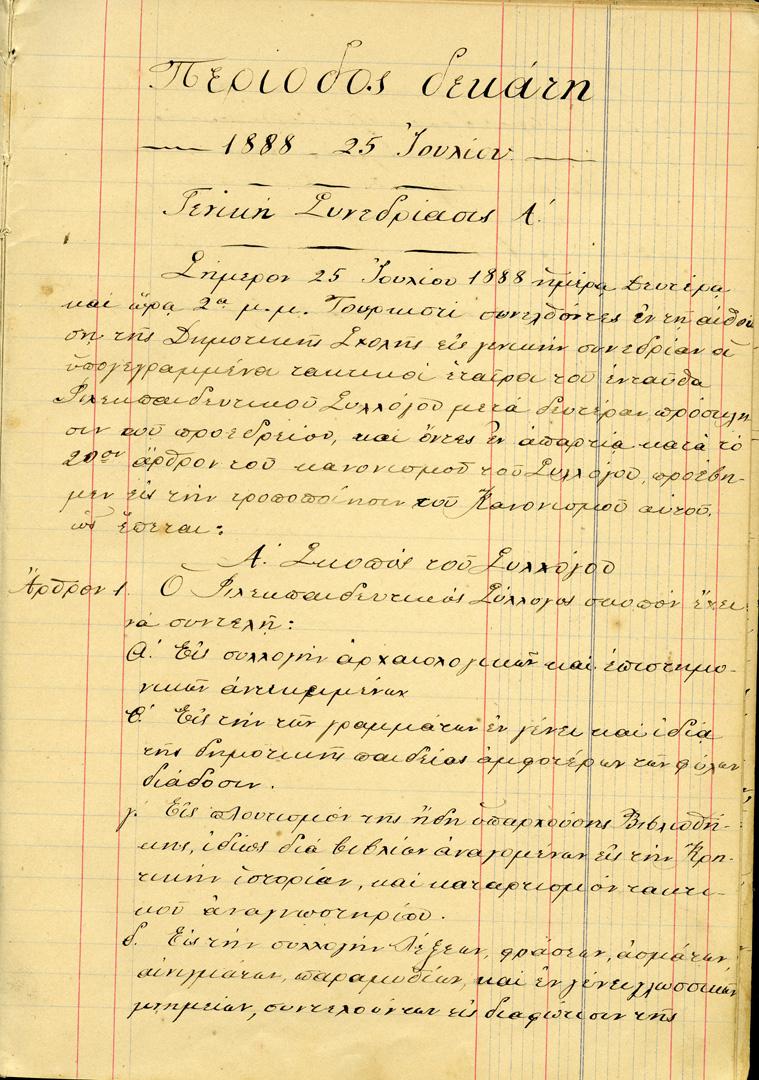

1888

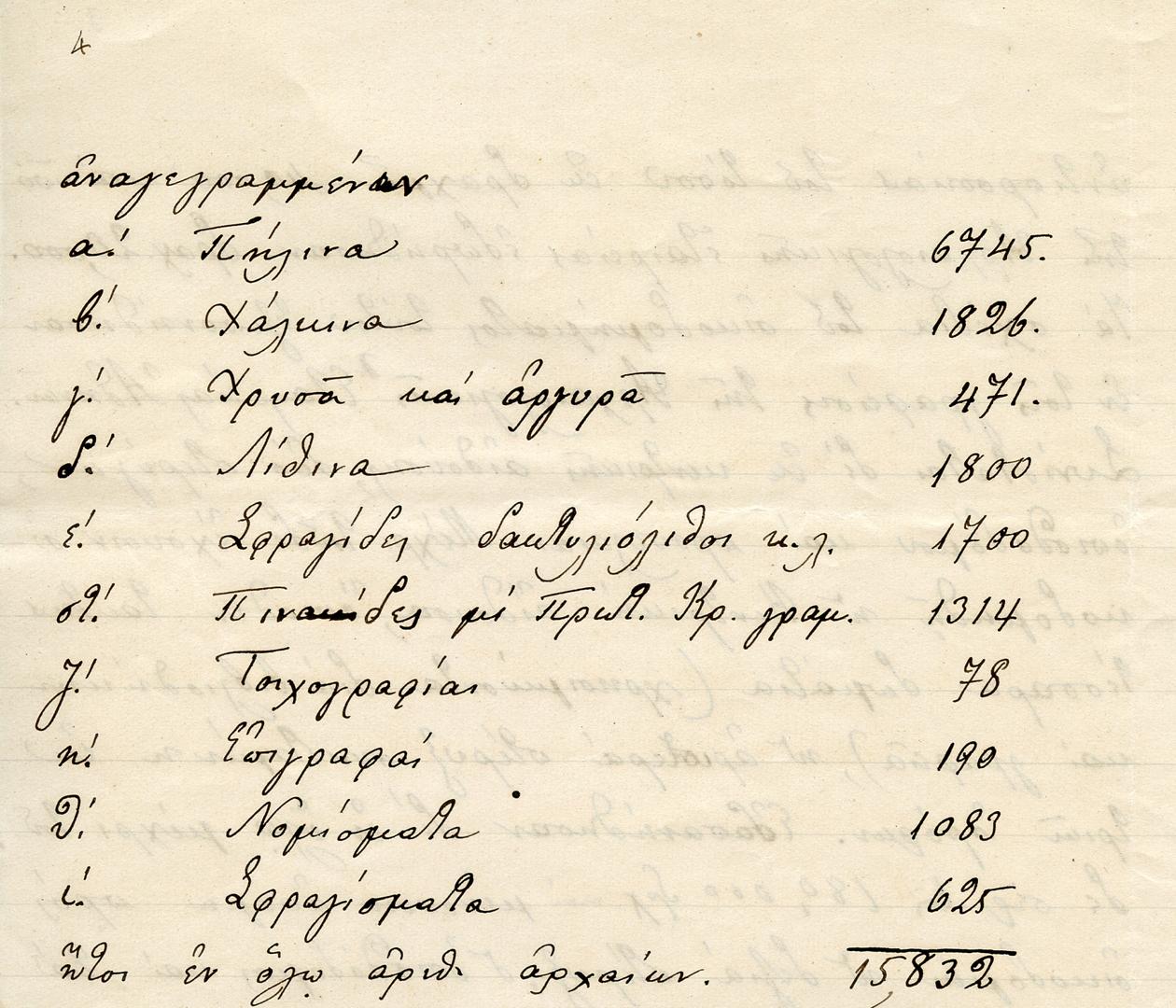

Publication of the first catalogue of the Museum of the Educational Society of Heraklion. One of the many steps towards the modern documentation of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum collections.

1896

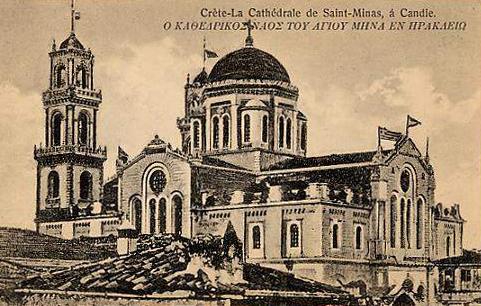

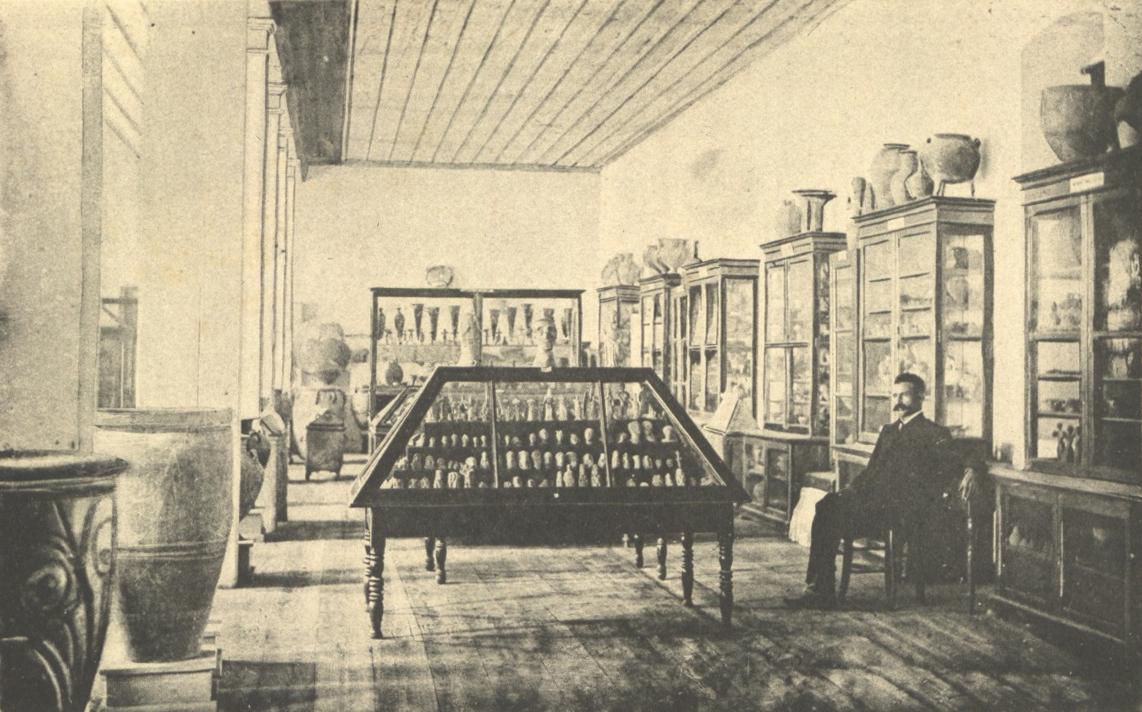

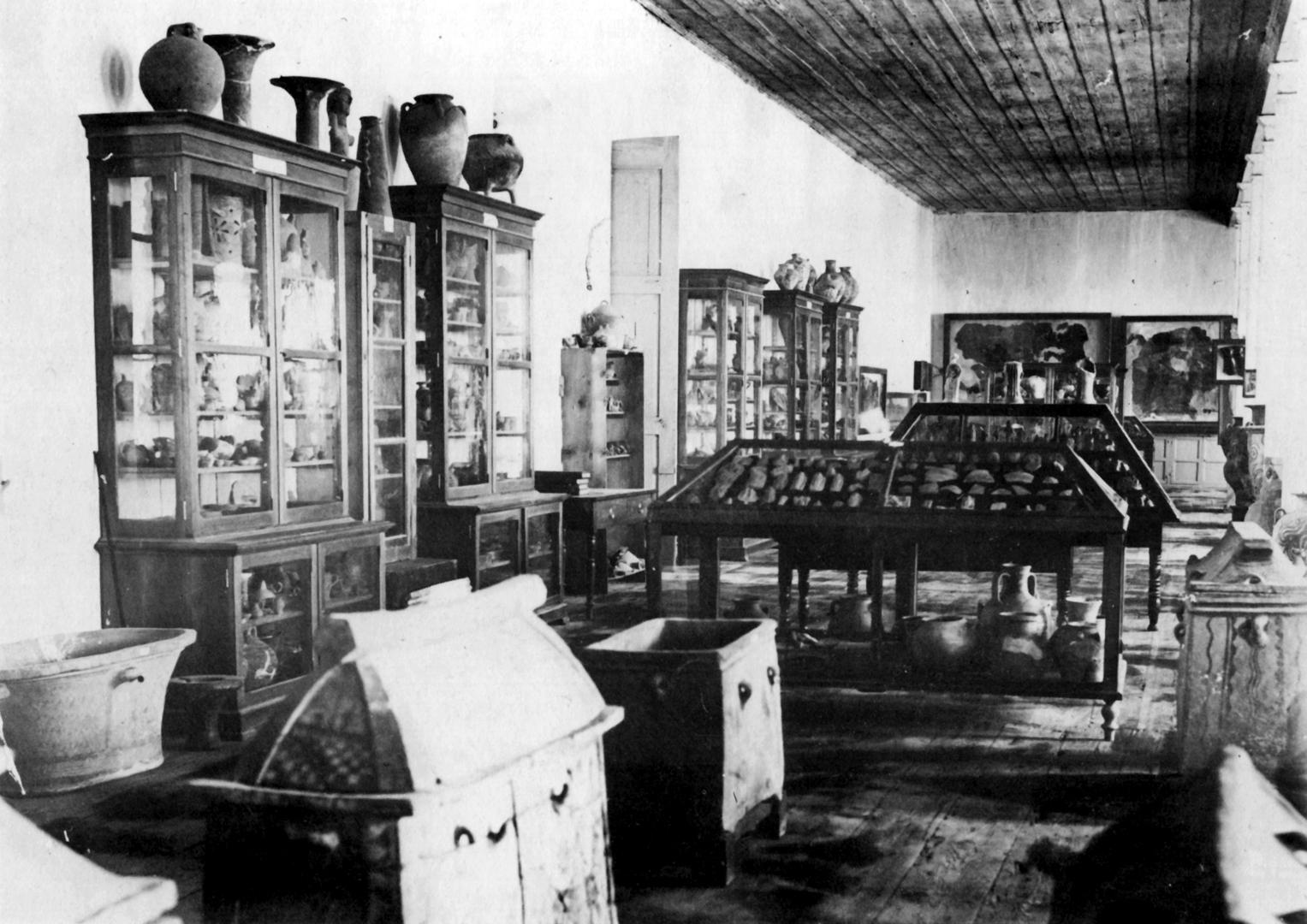

The antiquities preserved by the Educational Society of Heraklion were housed in two rooms, open to the public, in the courtyard of St Minas Cathedral. This was the safest place for them during the turbulent period preceding the collapse of Ottoman rule.

1897

Stephanos Xanthoudides (1863-1928), a philologist and autodidact archaeologist, was elected Secretary of the Educational Society, launching his vital efforts for the establishment of the Cretan Museum and the study of Cretan History and Prehistory. He and Iosif Hatzidakis were named the “Dioscuri of Cretan archaeology”.

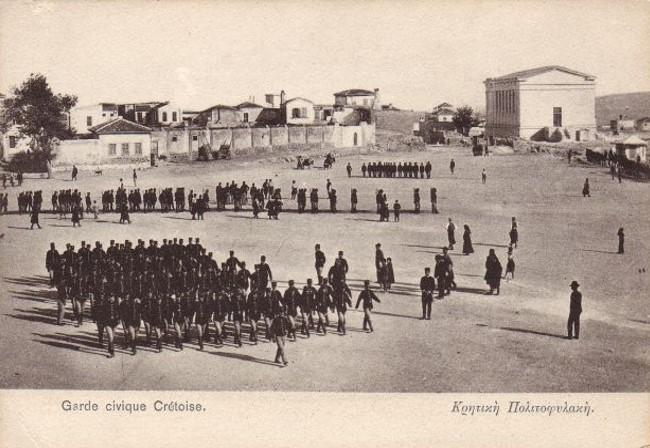

1898

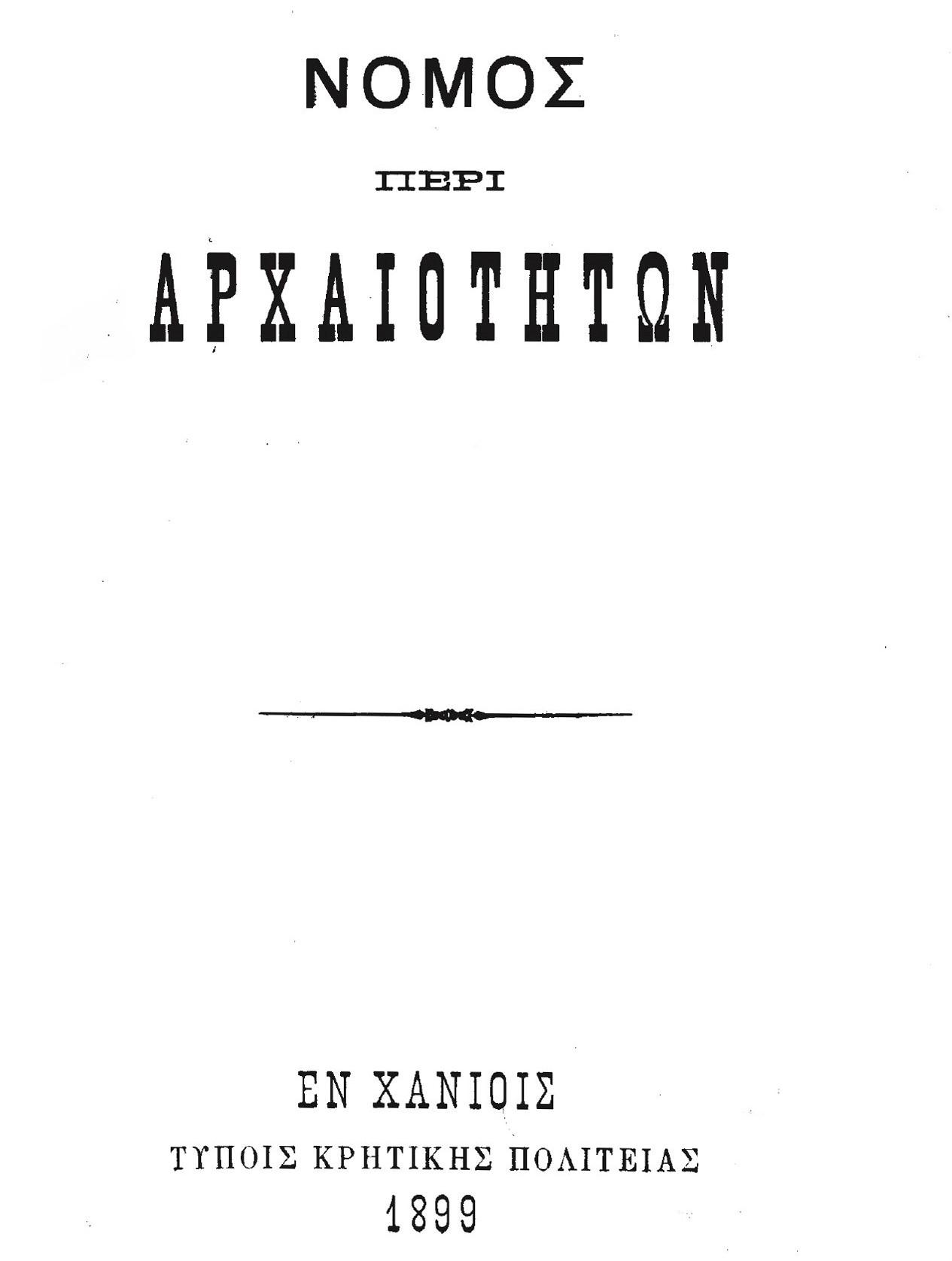

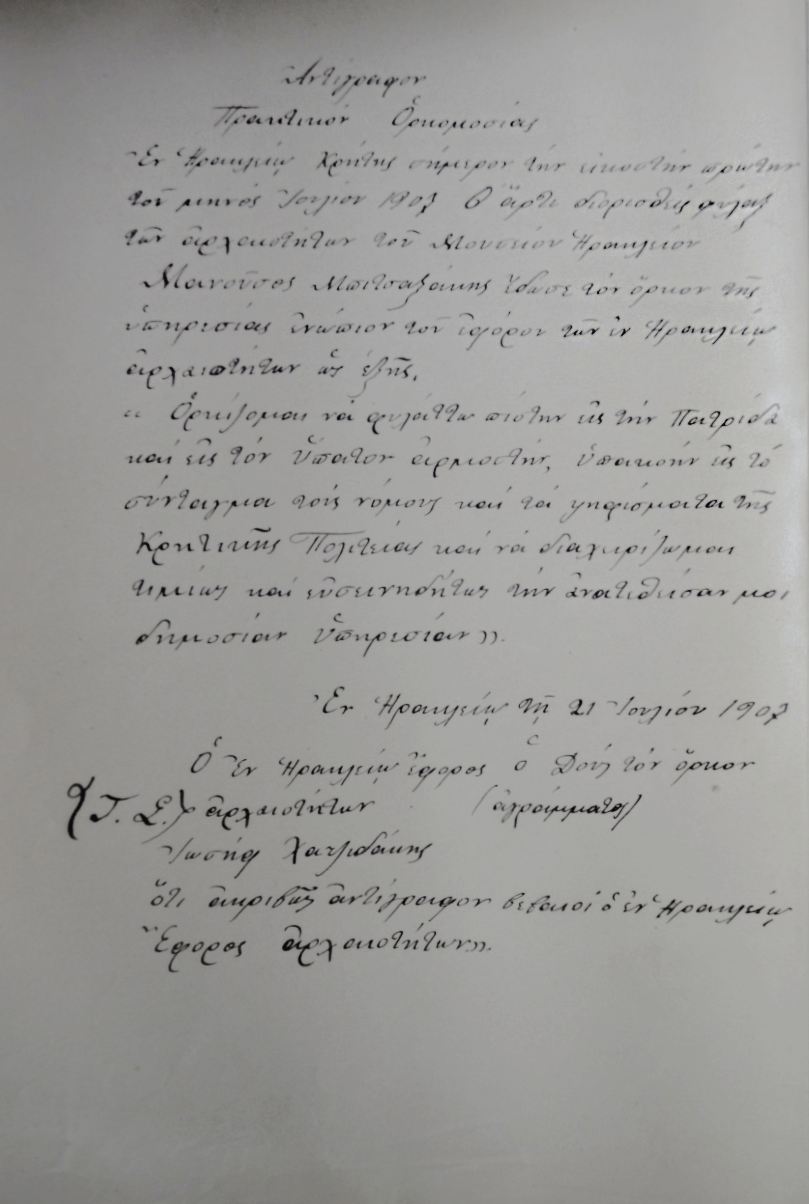

Crete breaks away from the Ottoman Empire and is declared an autonomous Cretan State. Under the “Law on Antiquities”, the Museum of the Educational Society of Heraklion is immediately ceded to the Cretan State. Iosif Hatzidakis is appointed its first Director.

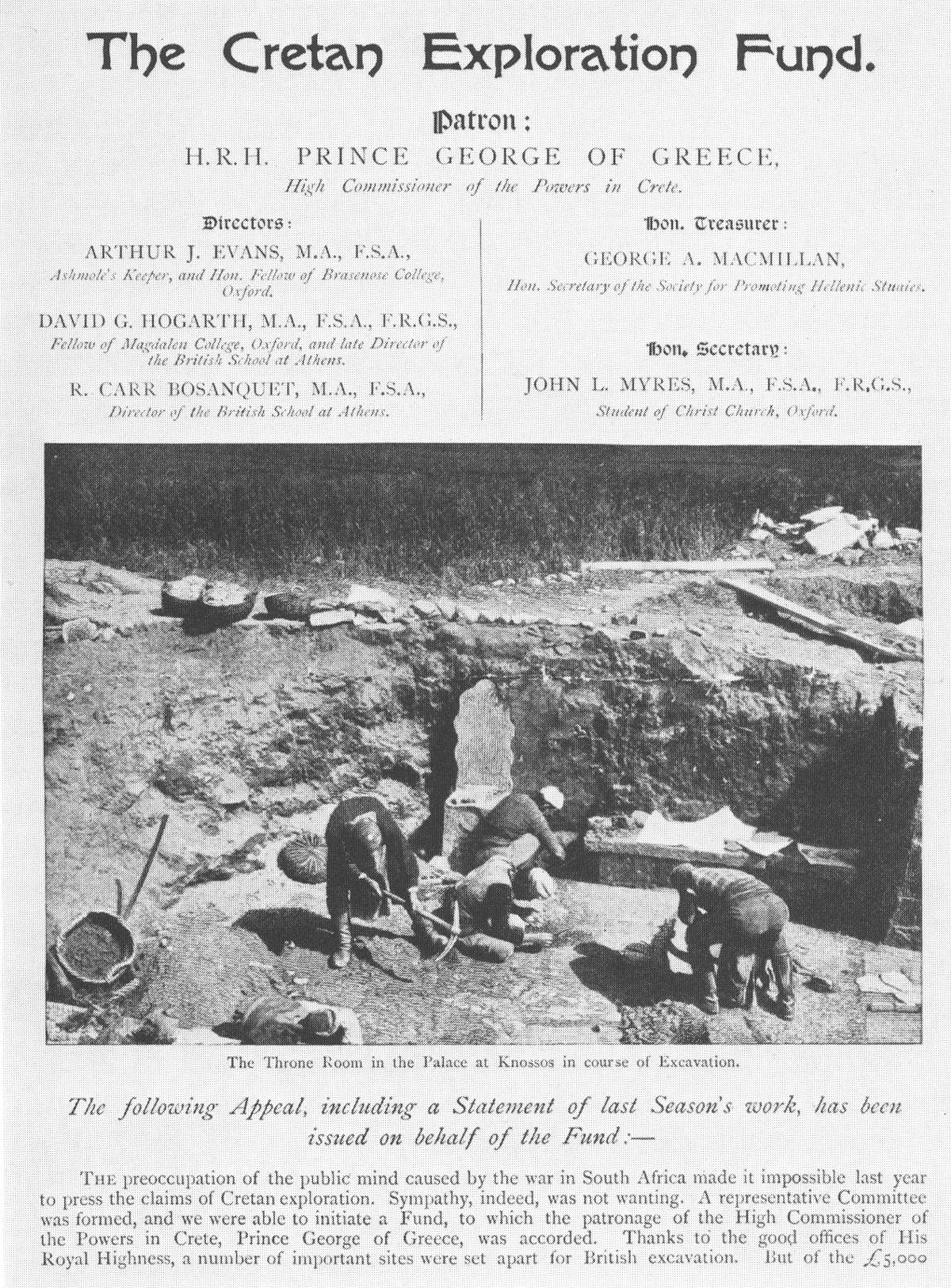

1900

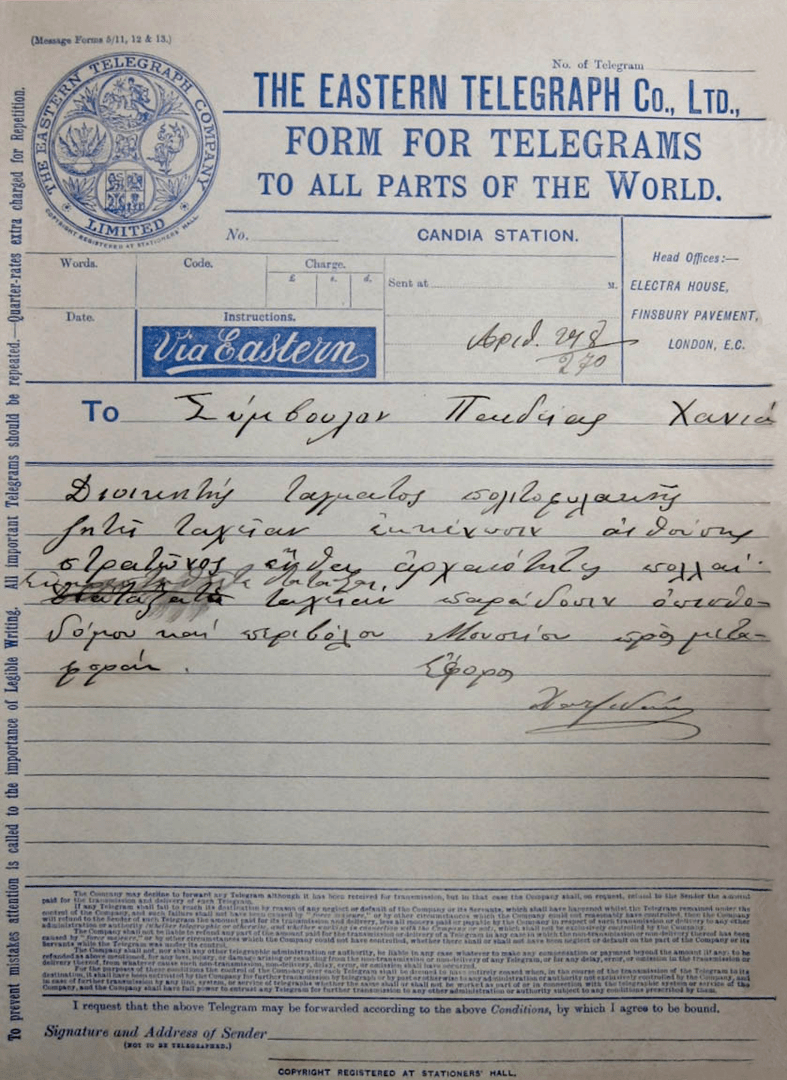

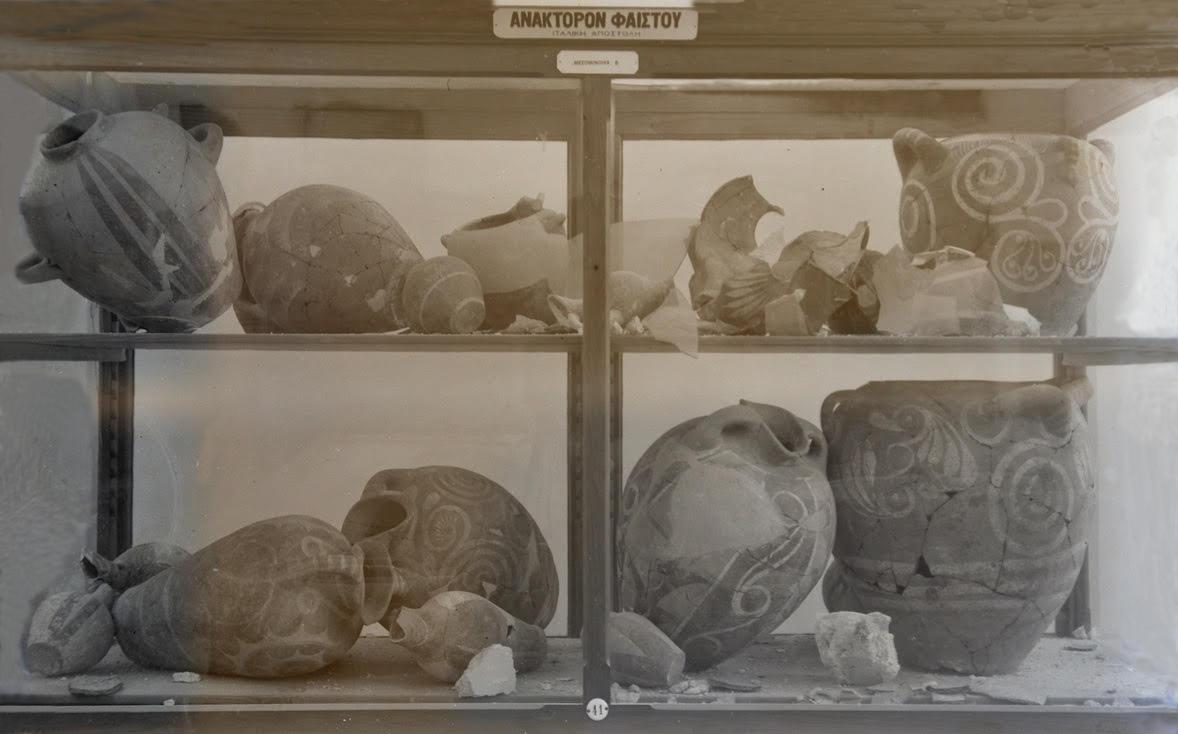

The foreign Schools of Archaeology and Archaeological Missions in Crete begin the Great Excavations. Countless archaeological finds come to light and are brought to the Cretan Museum, in accordance with Article 6 of the Archaeological Law enacted by the Cretan State.

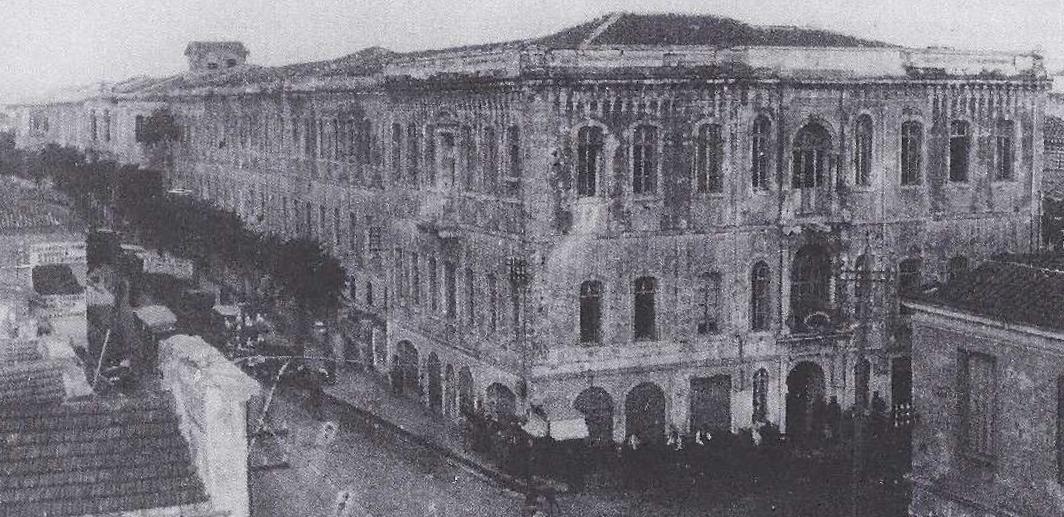

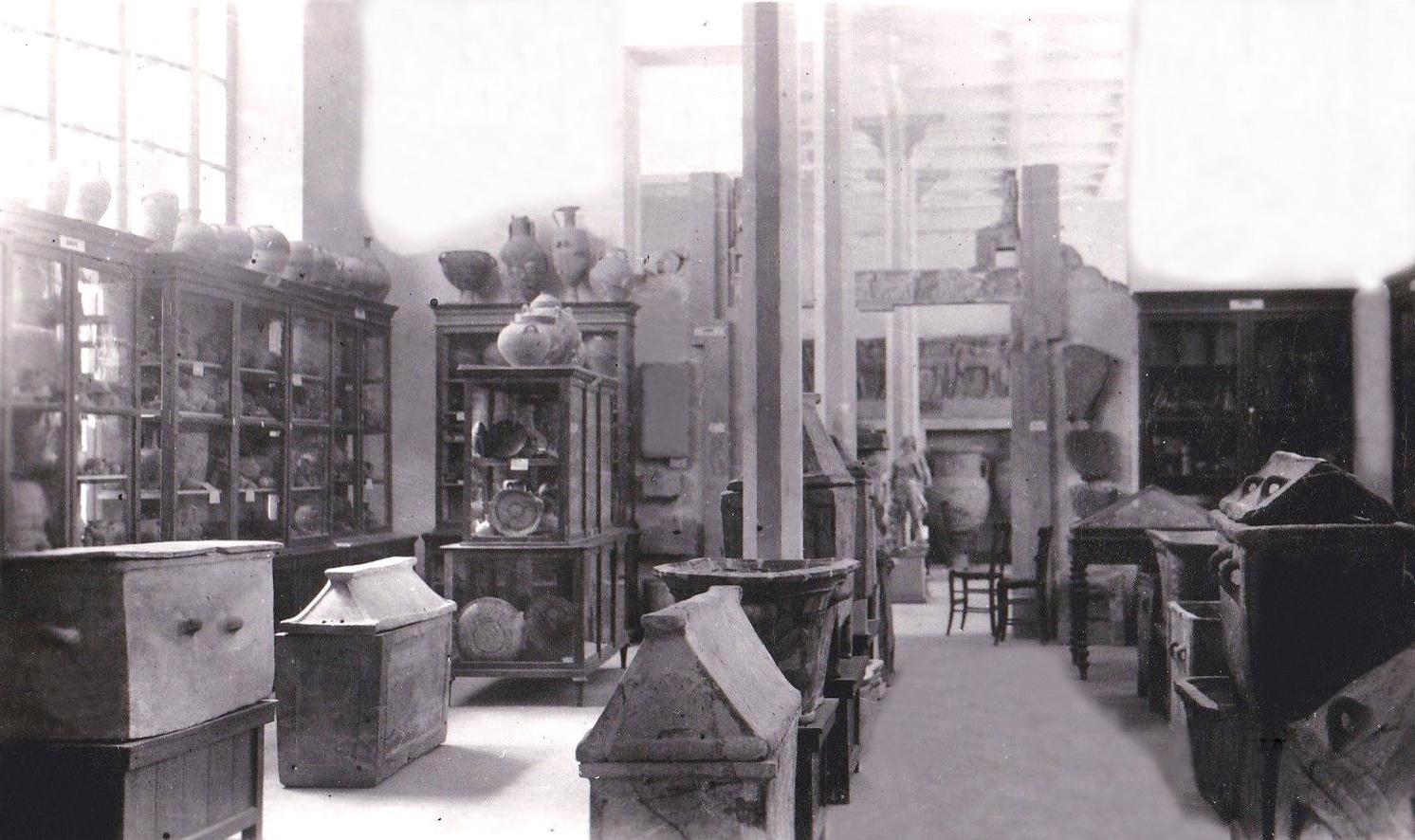

The two rooms in the courtyard of St Minas Cathedral are no longer large enough for the hundreds of antiquities being discovered. The Cretan Museum is temporarily housed in rooms in the former Turkish Barracks, now the Law Courts, a “very spacious but shabby” building according to Hatzidakis.

The Museum acquires new specialist staff. I. Zografakis and E. Saloustros, two of the first conservators of the Heraklion Museum, mark the start of a long, successful era of conservation and promotion of Cretan antiquities.

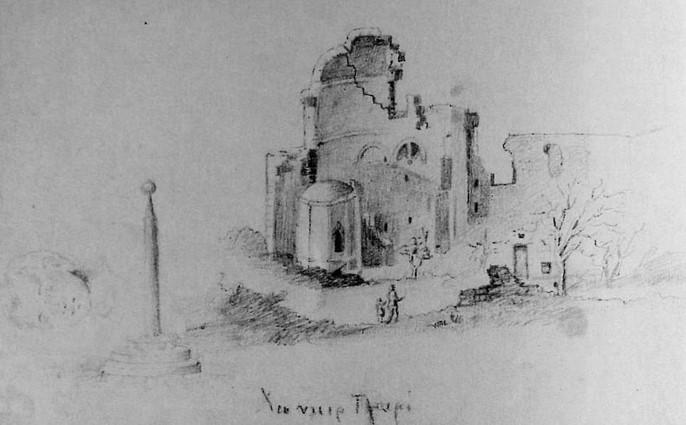

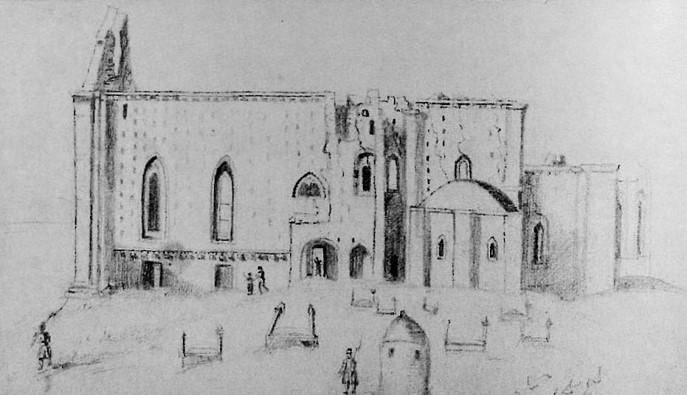

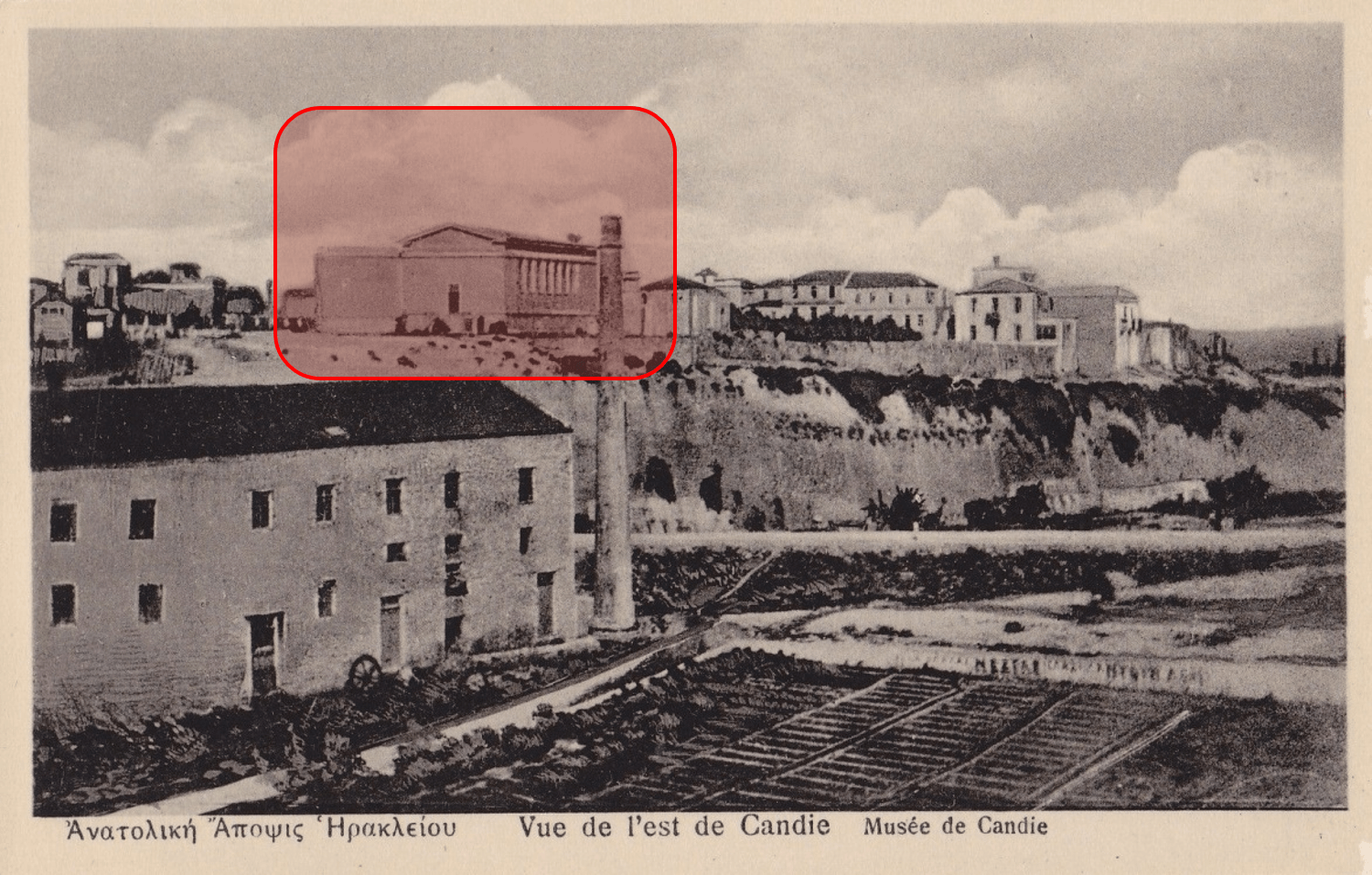

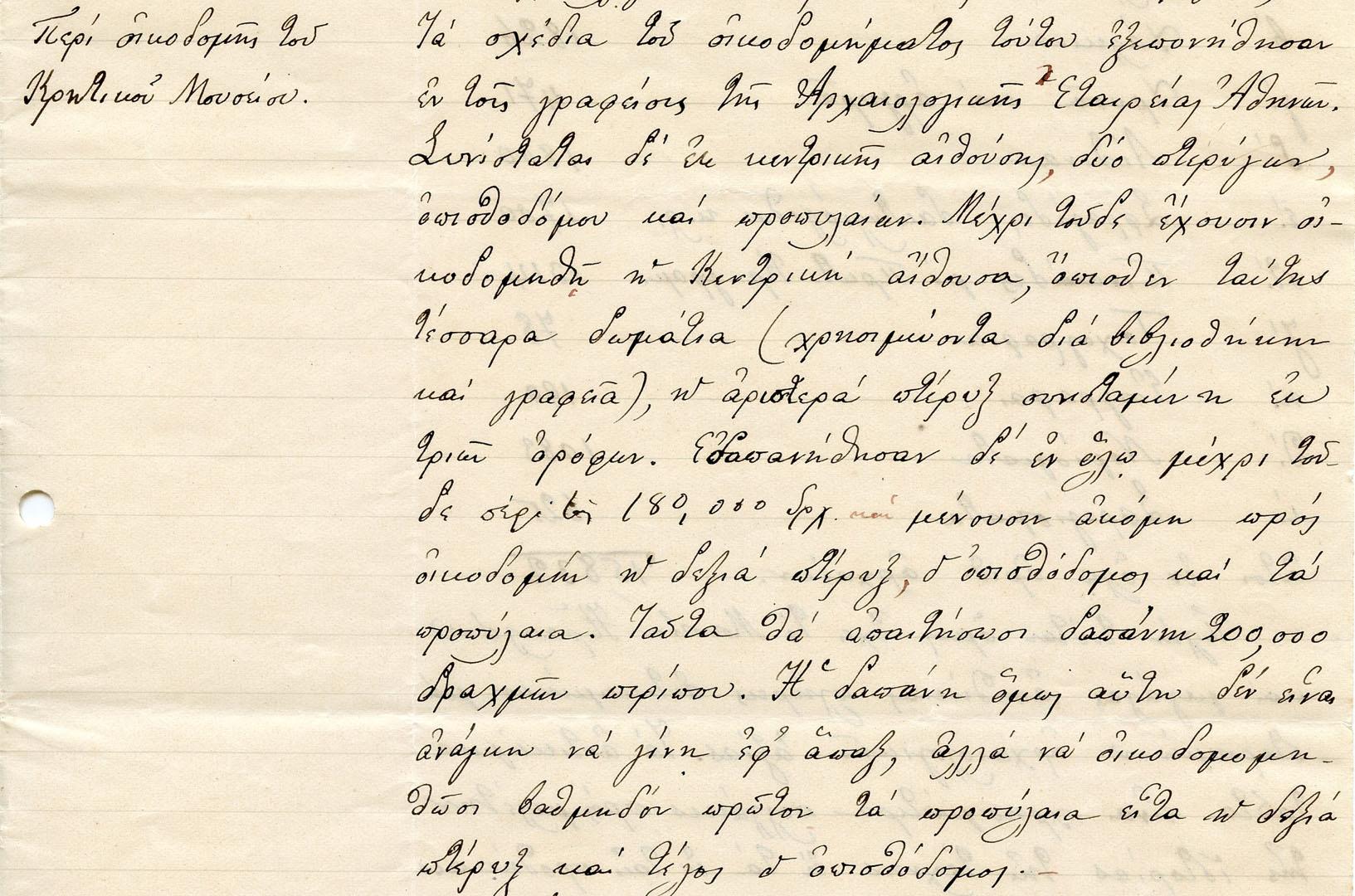

At Hatzidakis’s insistence, it was decided to erect a new building to house the antiquities, the offices and the laboratories of the Cretan Museum. The site selected was a landmark of Chandax (as Heraklion was formerly known): the hill on which lay the ruins of the Franciscan Friary of St Francis and the surviving chapel, which had been converted into the Imperial Mosque. The decision was given impetus by a donation by Gaston Arnaud-Jeanti, a fervent champion of the “Cretan Question”.

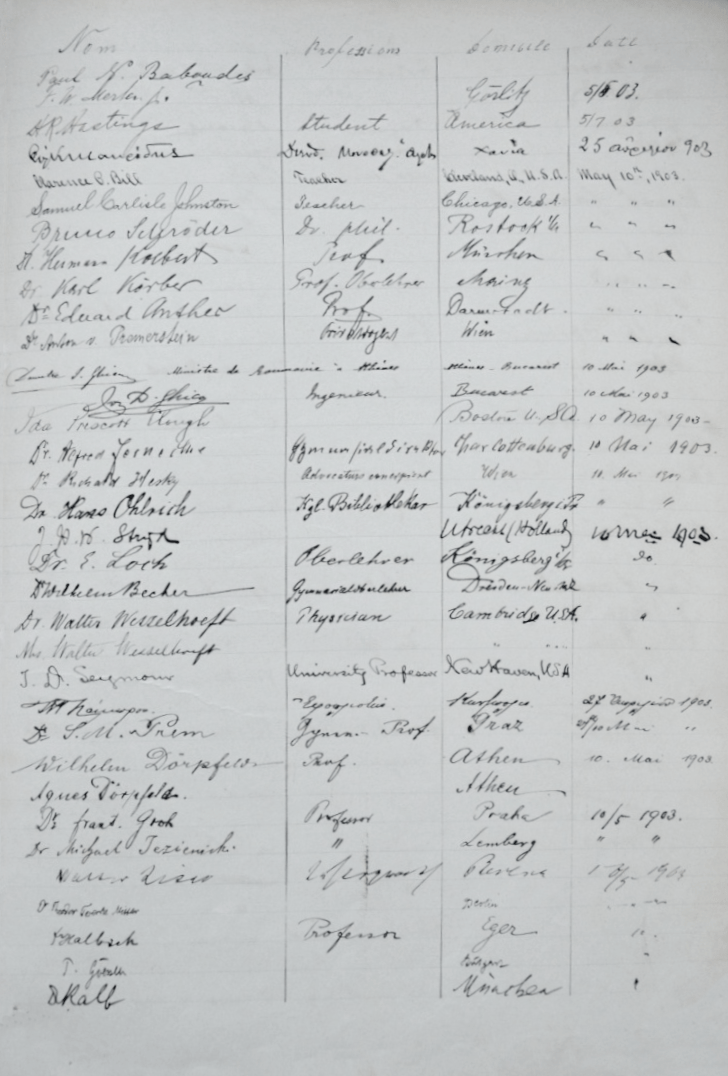

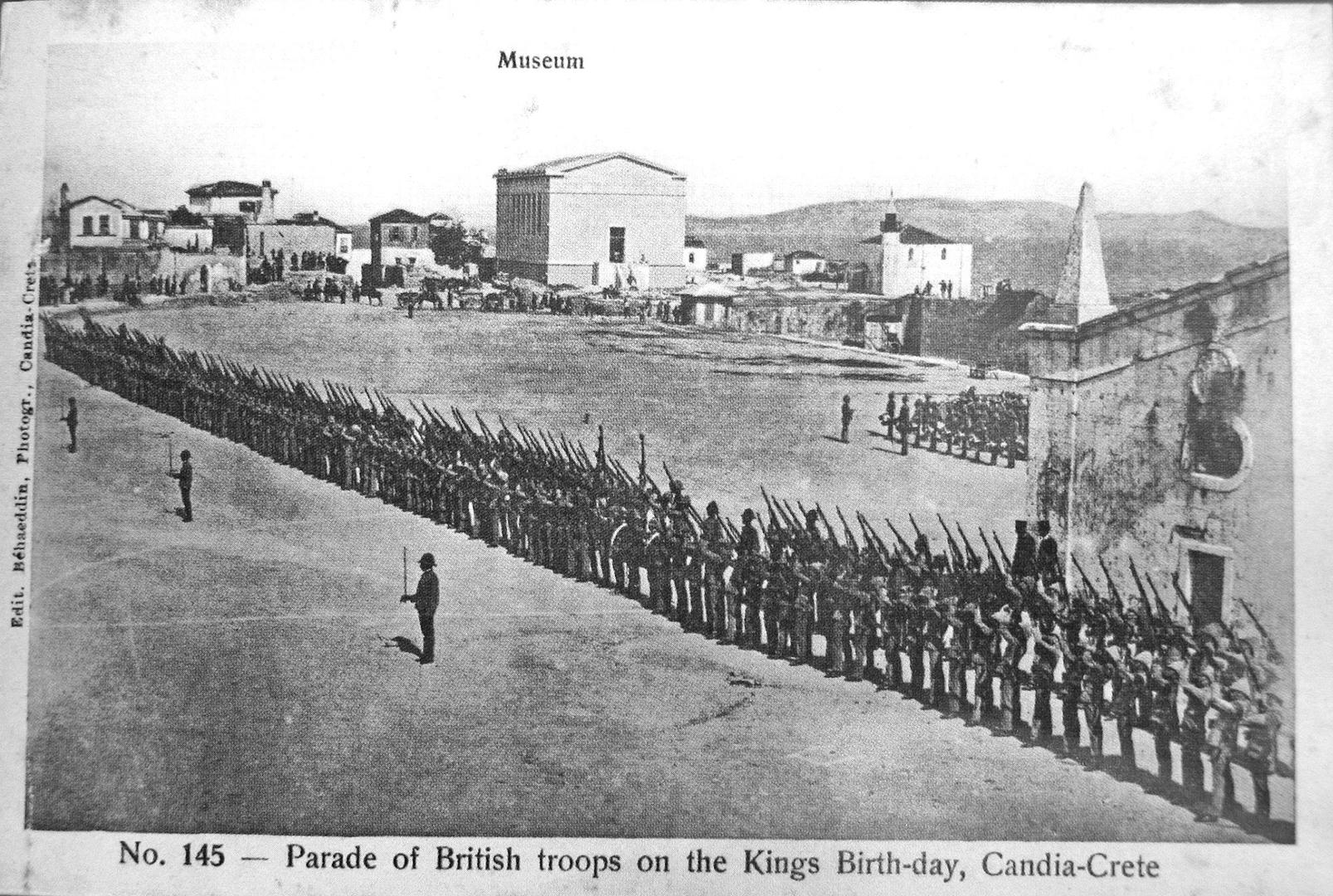

1903

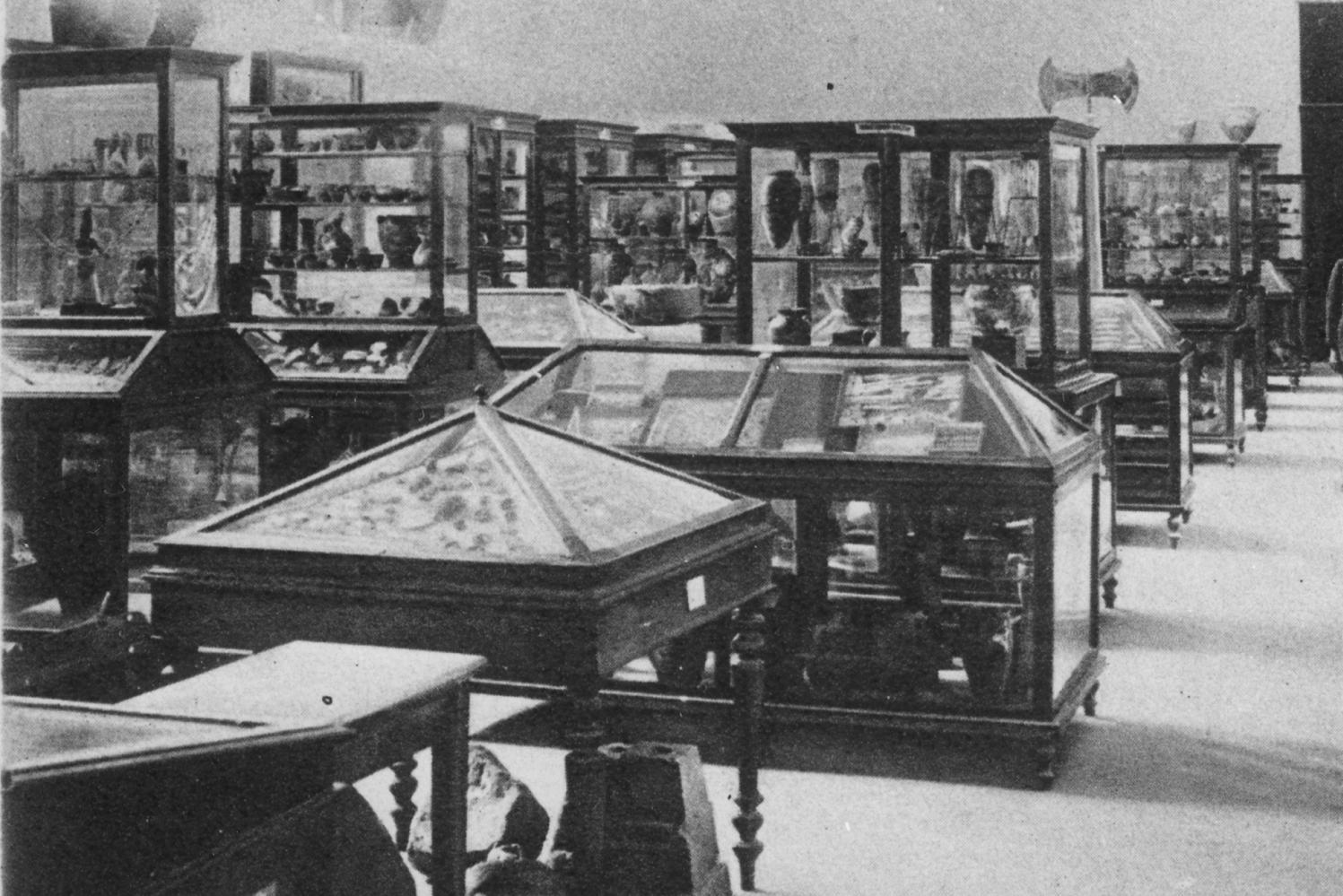

While still housed in the Barracks, the Cretan Museum rapidly became a popular destination. Together with the archaeological site of Knossos, it became a required stop on tours of the East.

1904

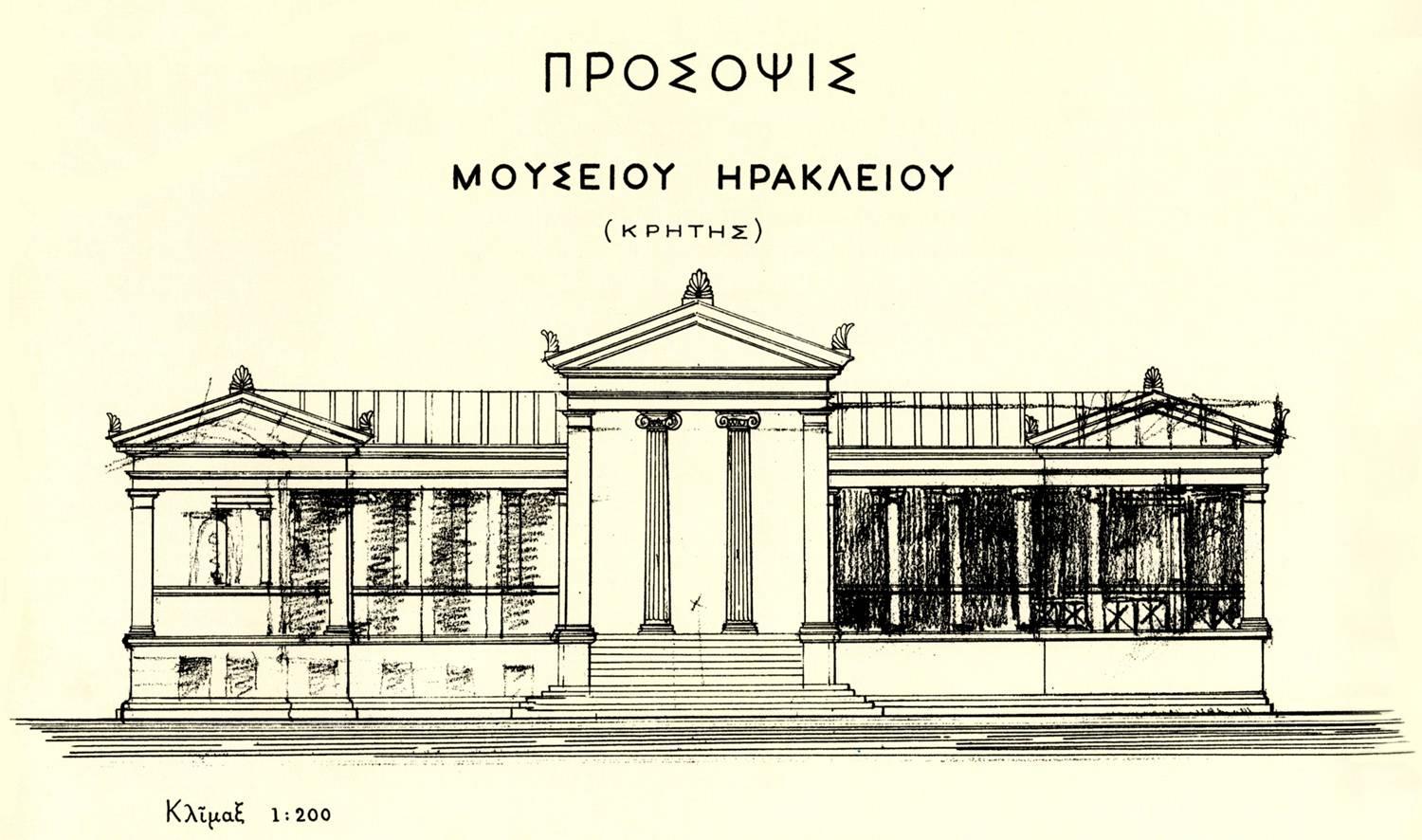

The foundation stone ceremony of the first purpose-built Heraklion Archaeological Museum was held in October 1904.

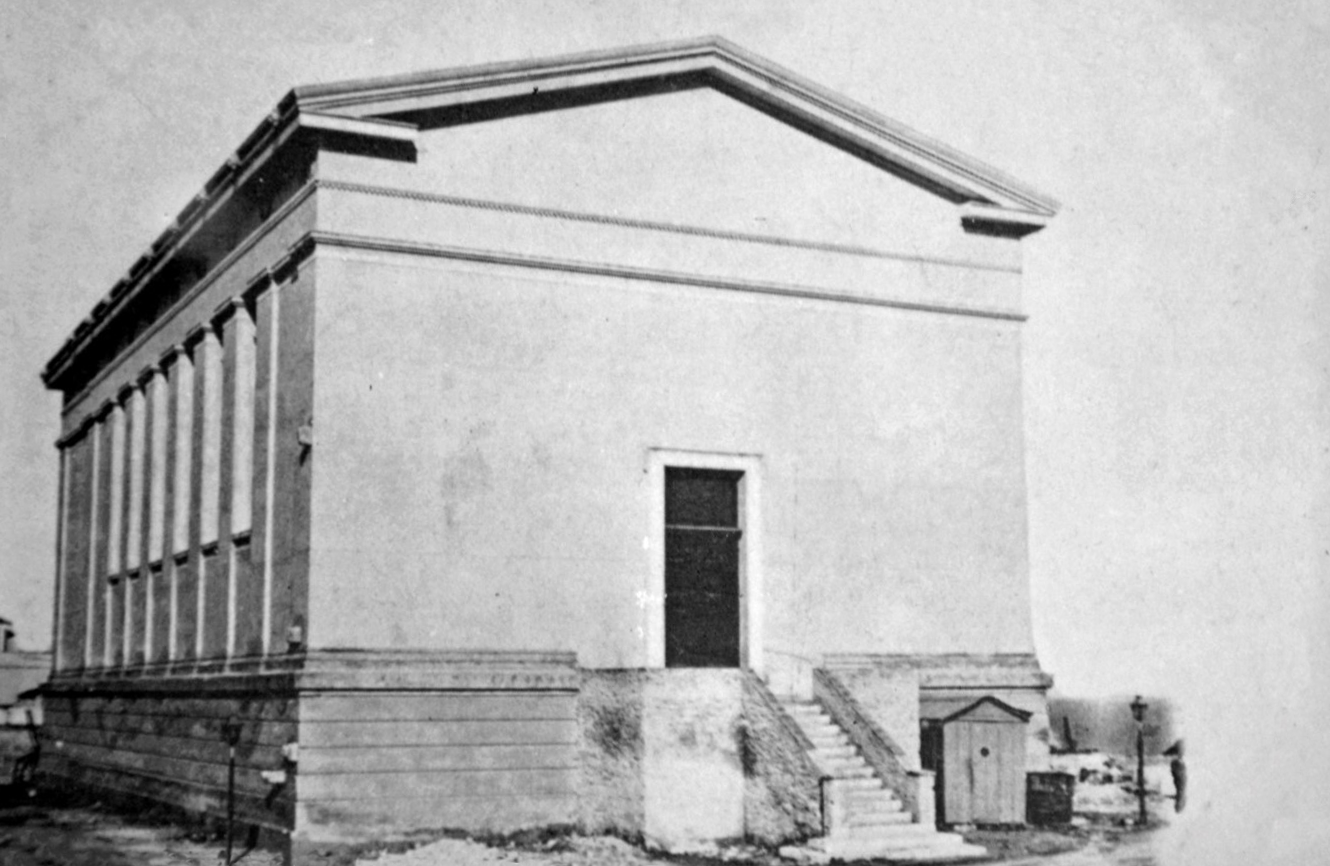

The proposed design by the German archaeologist and architect W. Dörpfeld and P. Kavvadias, the General Ephor of Antiquities of Greece, did not take the nature of the Cretan antiquities into account. The ambitious design in the Classical style was only partially implemented.

.

1907

The central hall of the new Museum was delivered in 1907, followed by the rear hall and the roofed shelter in the courtyard the following year. The transfer of the antiquities from the Barracks was completed.

1912

The West Hall of the Museum was completed in 1912.

1914

On 1 December 1913 Crete was united with Greece once and for all. Greek Archaeological Law was implemented on Crete. Museum with Knossos were organized in the 9th Archeological Region, under the direction of Iosif Hatzidakis.

Huge numbers of new finds from excavations in Central and East Crete were added to the Museum collection. They were conserved, recorded and added to the Exhibition, while many pieces, chiefly sherds, were arranged in the storerooms. Five new display cases for the new finds were placed in the Central Minoan Hall. The Museum was becoming uncomfortably crowded. It was clear that the building urgently needed to be completed according to the original plan, as it had been only half built before the Union with Greece.

1923

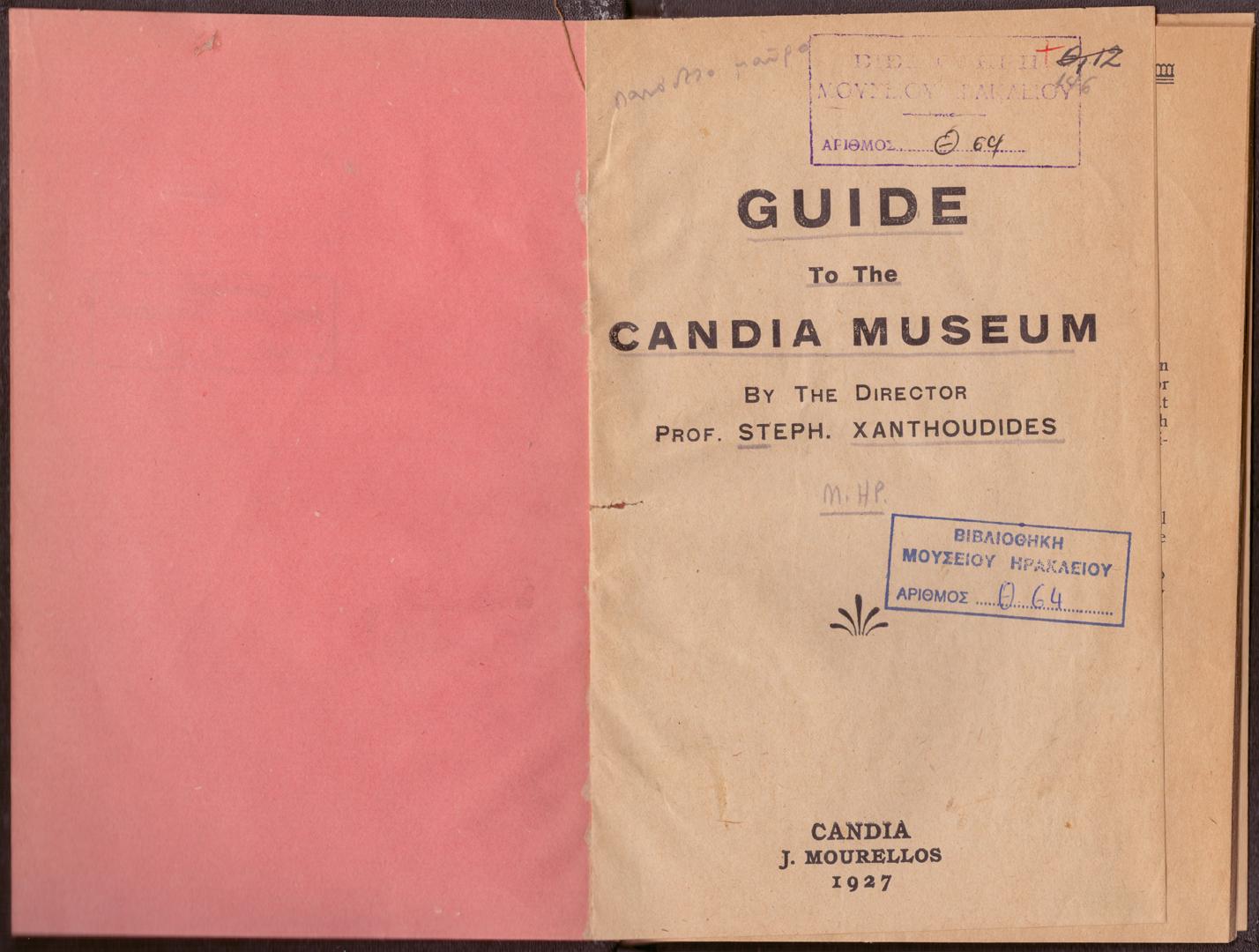

On 2 July 1923 Stephanos Xanthoudides (1863-1928) was appointed Director of the Heraklion Museum.

1927

Guide to the Exhibition by Director Stephanos Xanthoudides. The English edition was addressed to the large non-Greek-speaking public.

1928

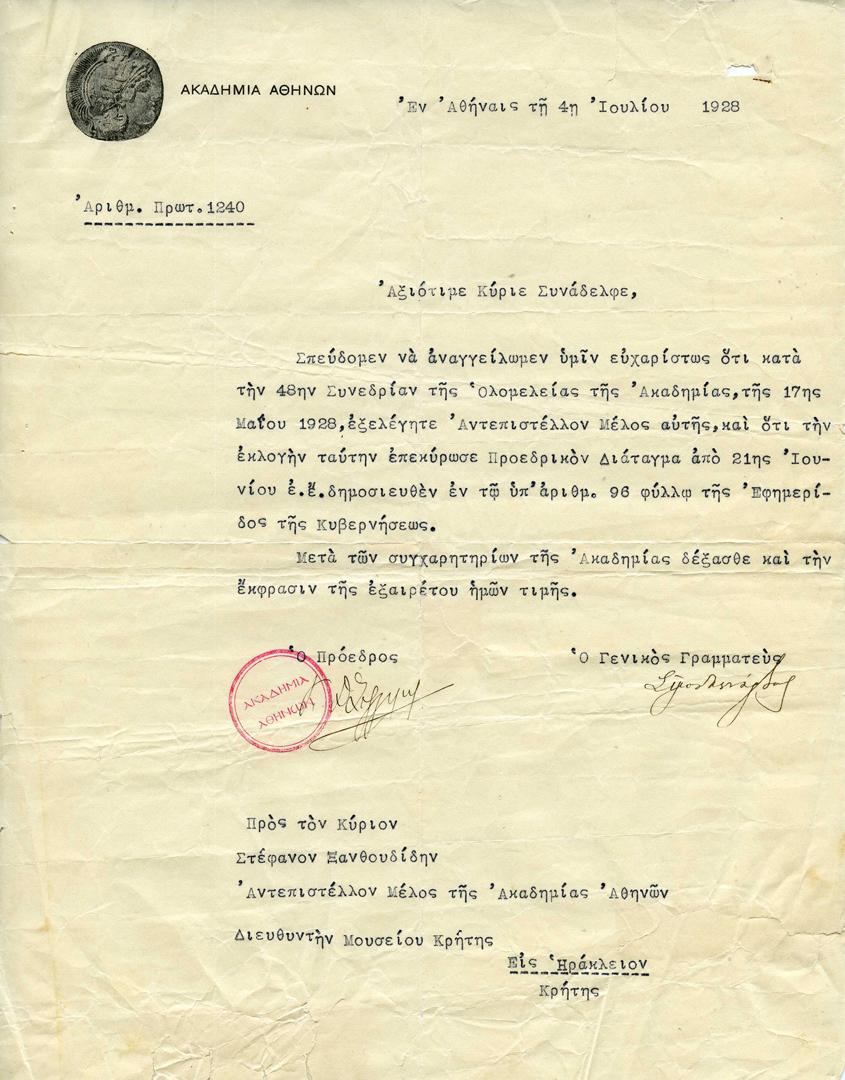

Stephanos Xanthoudides died unexpectedly on 18 September 1928. Shortly before his death, he had been made a Corresponding Member of the Academy of Athens, an honour also bestowed on his successor Spyridon Marinatos.

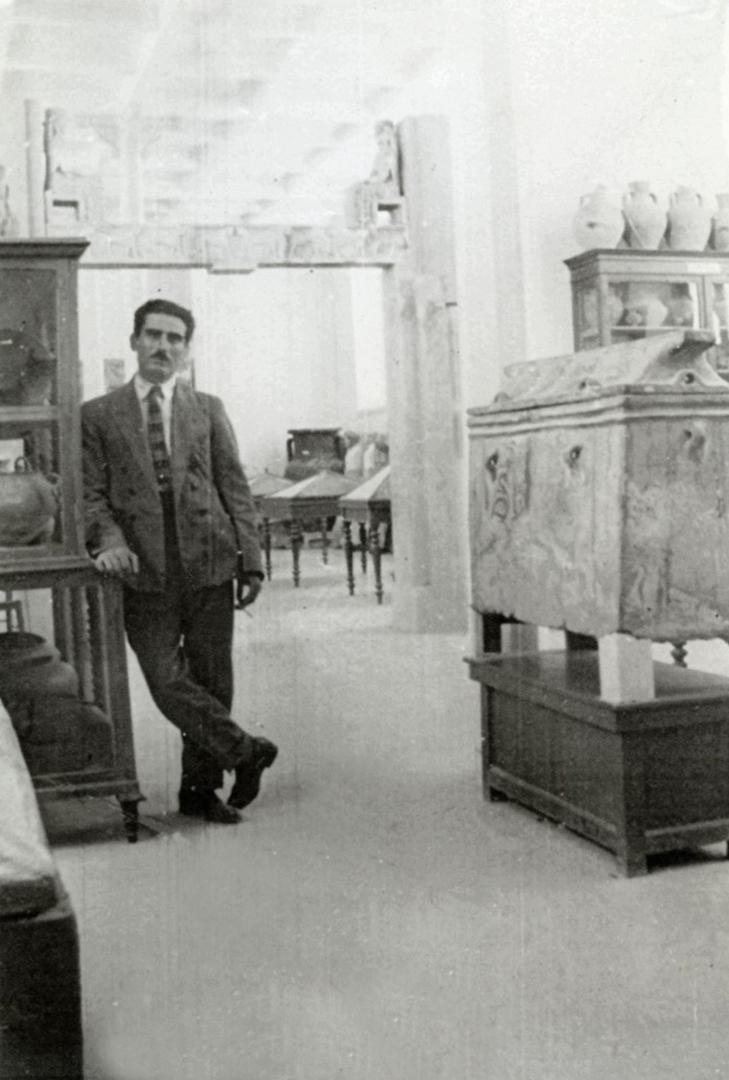

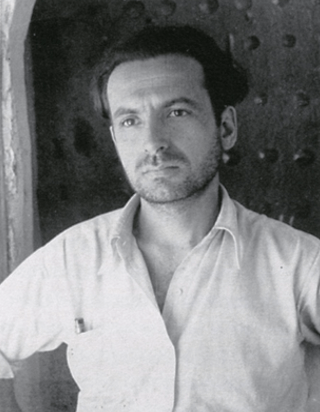

Spyridon Marinatos (1901-1974) was appointed Director of the Heraklion Museum at 28 years of age. He actively linked the Museum to tourism, which had been boosted between the wars. The Museum was already a popular international destination.

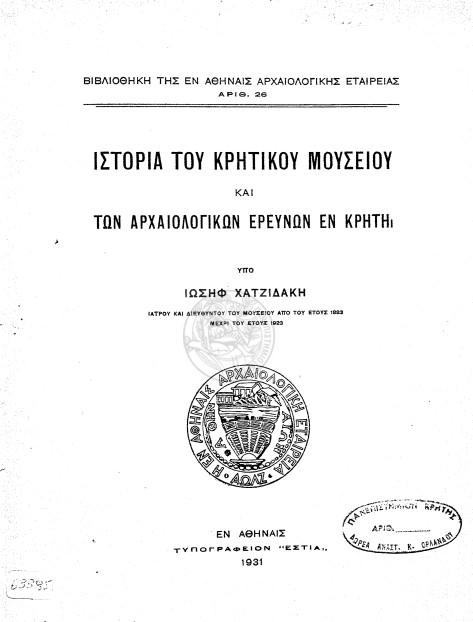

1931

A few years before his death, Iosif Hatzidakis, “although burdened by age and suffering from a tortuous illness”, wrote an account of the history of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum as he had experienced it and helped to shape it from 1883 to 1930.

The deaths of Hatzidakis and Xanthoudides, and the demolition of the old building a few years later, marked the end of an era and the beginning of a new one in the history of the Museum.

1935

On February 25, 1935, a strong earthquake hit Heraklion, adding to previous earthquakes of 1911, 1926 and 1930. Destruction and damage to dozens of exhibits and the building itself needed immediate action.

With the support of Education Ministry architect Patroklos Karantinos, Marinatos managed, despite opposition, to secure approval for the demolition of the Neoclassical building and its replacement with a modern anti-seismic structure on the same site. This solution was considered more appropriate than completing the existing unsuitable building.

By December 1935, the demolition of the old building was almost complete and work began on the new building.

The plans for the new Museum were commissioned by the Ministry of Education to Patroklos Karantinos, architect of the 1930s and representative of modernism in Greece.

1937

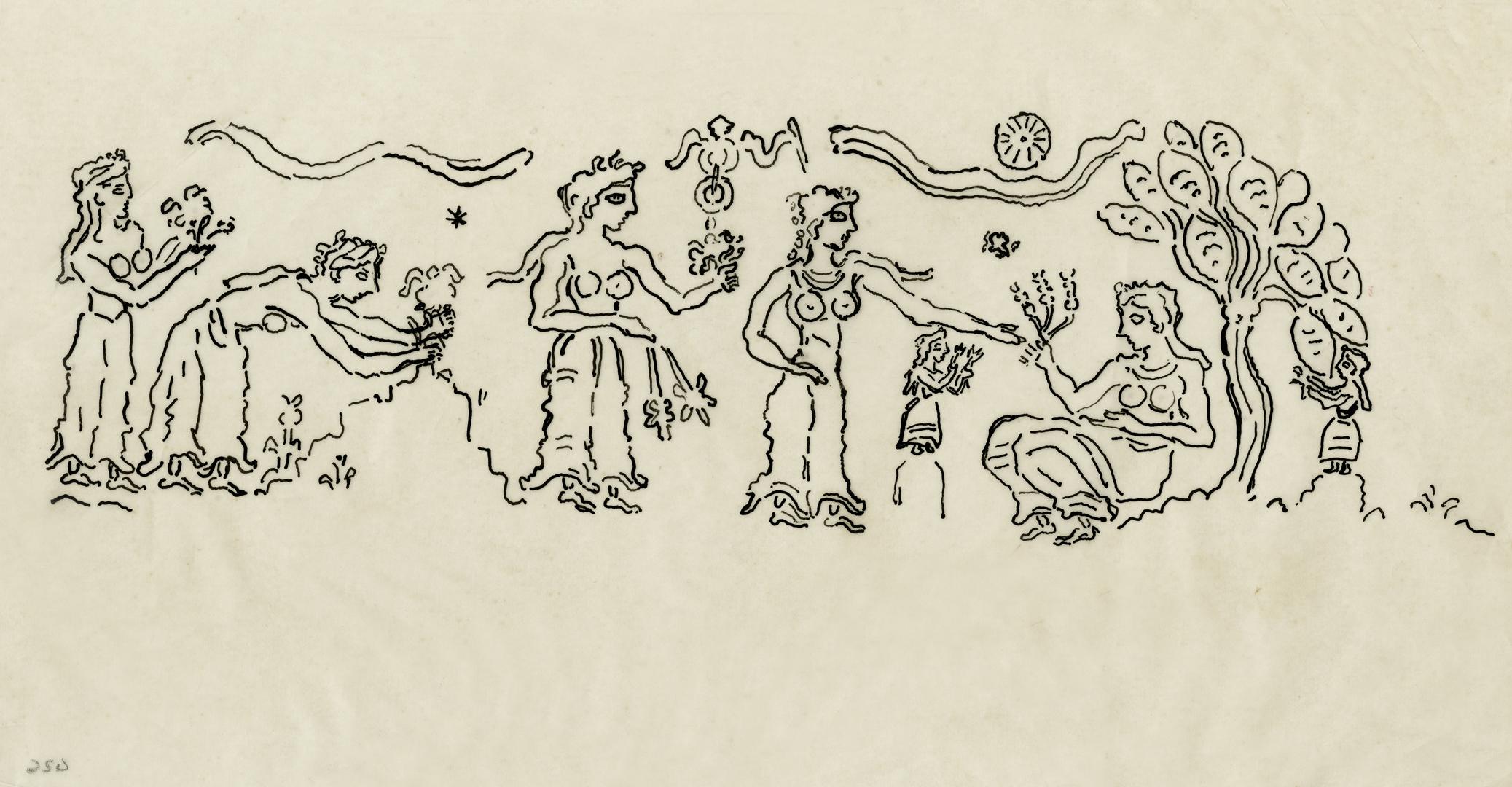

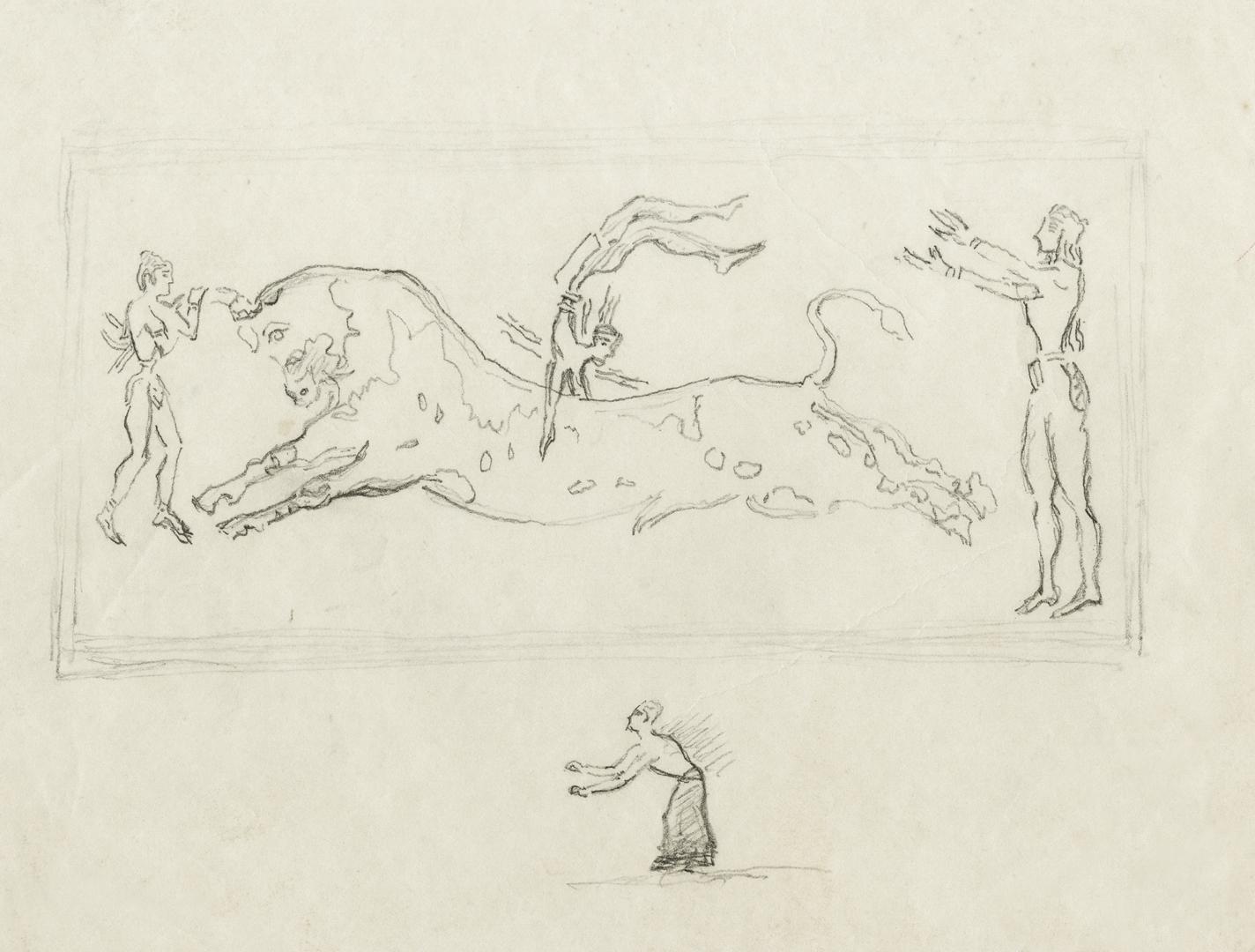

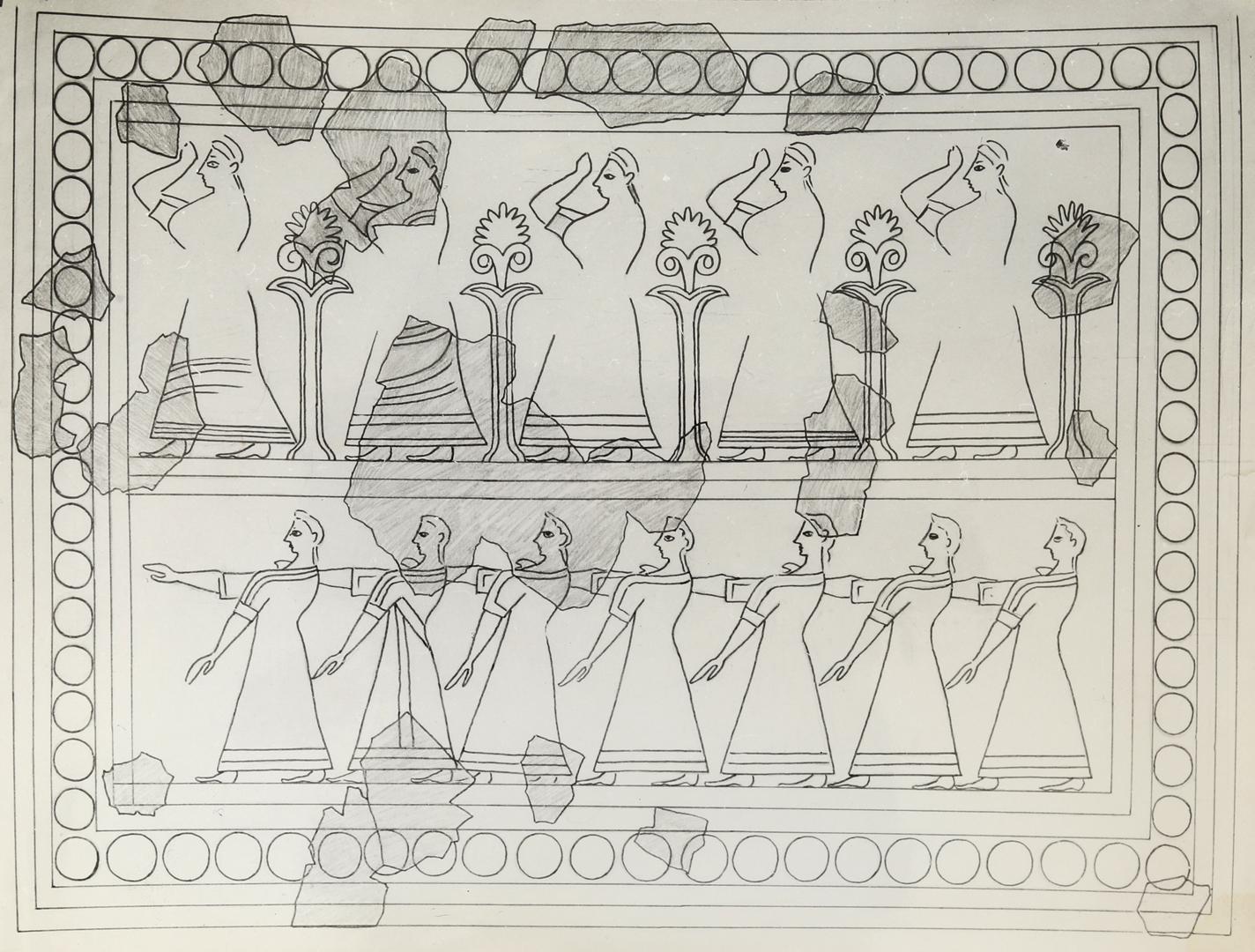

Patroklos Karantinos suggested that artist Spyros Papaloukas, a student of Konstantinos Parthenis and the official war artist of the Asia Minor Expedition, undertake the decoration of the façade of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. The mural was to cover the large L-shaped portico at the main entrance to the Museum. The artist studied prehistoric Cretan art and drew up his proposal. The drafts and maquettes survive but the work was interrupted by the Second World War and ultimately abandoned

1938

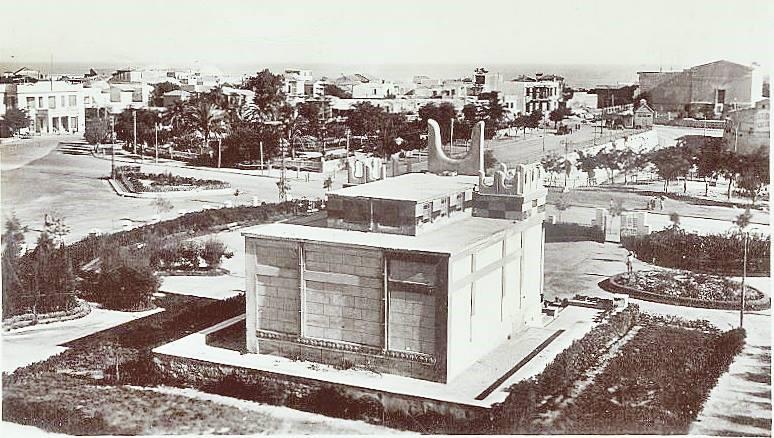

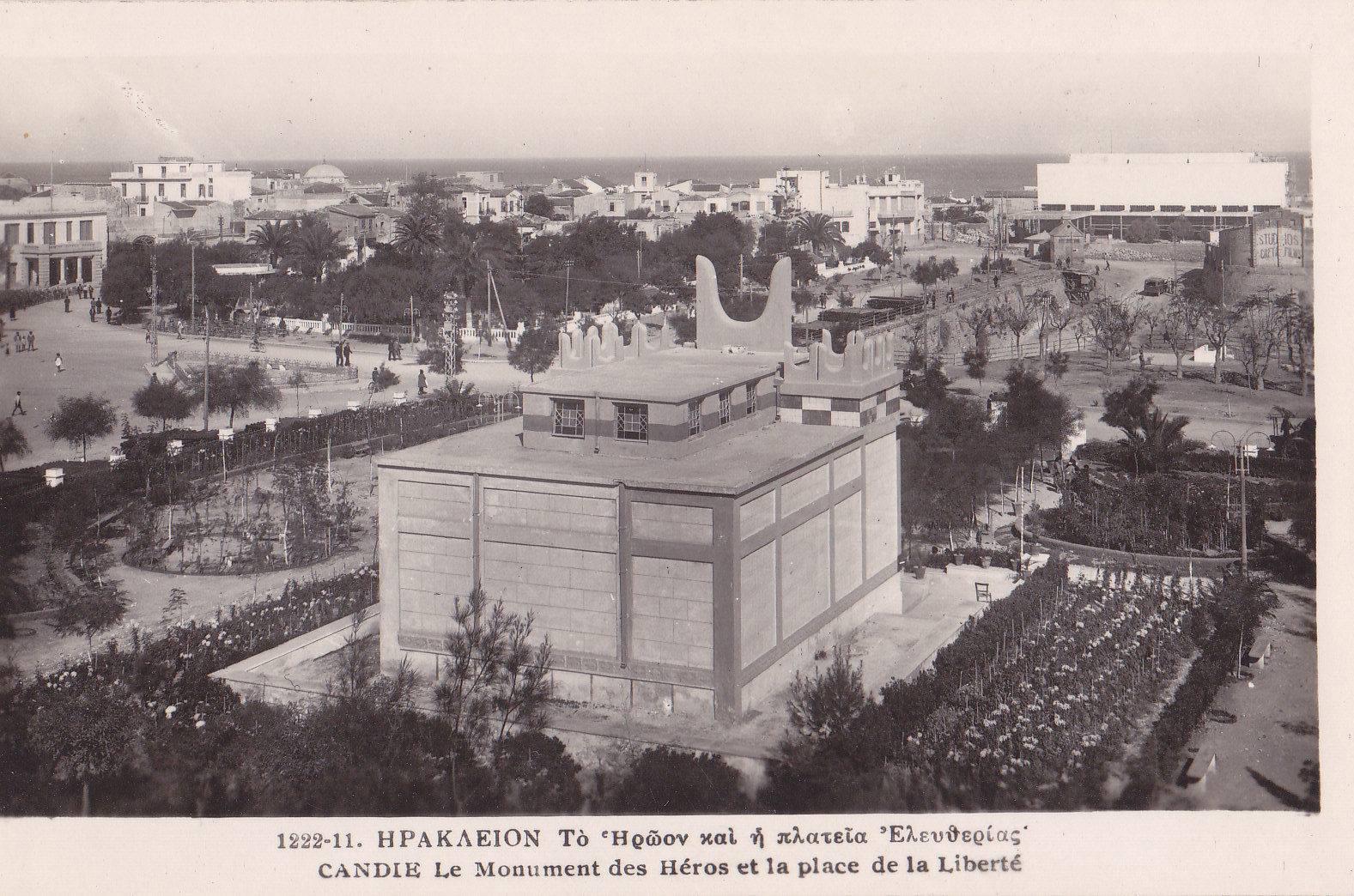

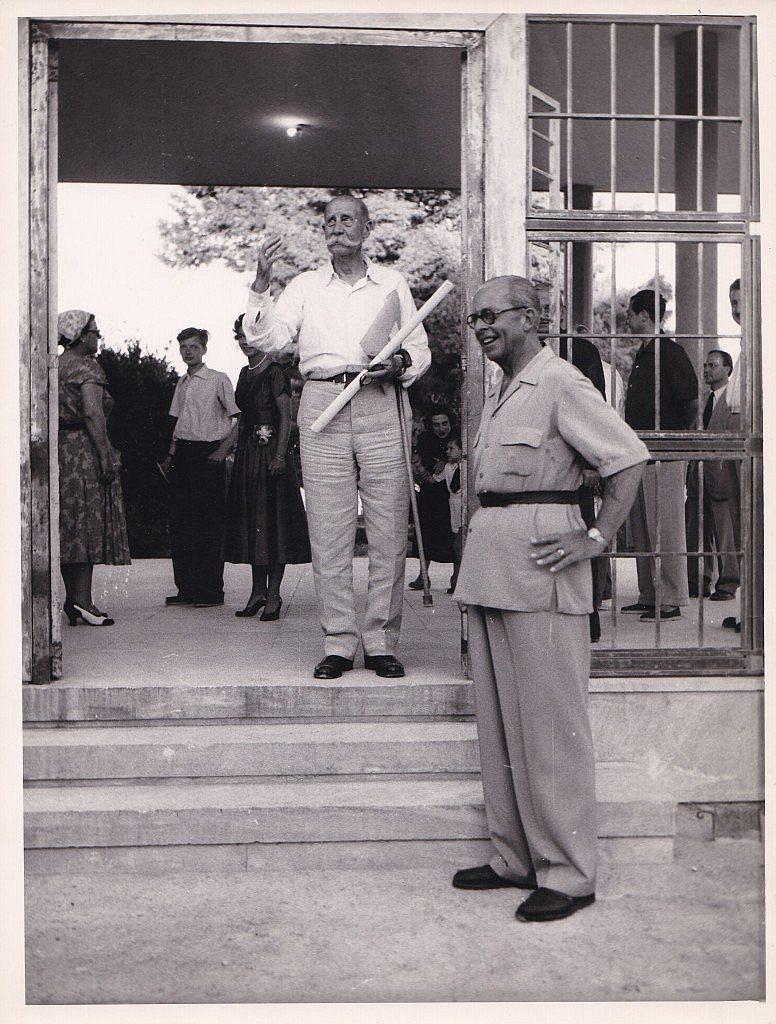

The first wing of the building was completed. It had seven galleries on the ground floor and five on the upper floor, with a total area of 8,800 m2 and a volume of 26,800 m3.

The antiquities were moved into the new building between 24 January and 9 February, and the newly built Museum opened to the public on Sunday 27 February 1938.

“A glorious edifice in the structurally lustreless city of Heraklion”, a typical example of Modernist architecture between the wars.

The innovative addition of an underground air-raid shelter meant that a few years later, during the bombings by the German army of occupation, most of the antiquities of the Museum were saved.

When Marinatos was appointed Director of Antiquities and left Heraklion, the work was overseen by Christos Petrou-Mesogeitis (1909-1944), an archaeologist from Kalyvia in Attica, who worked at the Heraklion Museum from 1937 to 1939.

1940

Nikolaos Platon (1909-1992) was appointed curator of the 9th archaeological district and director of the Heraklion Museum, almost at the same time as the start of World War II

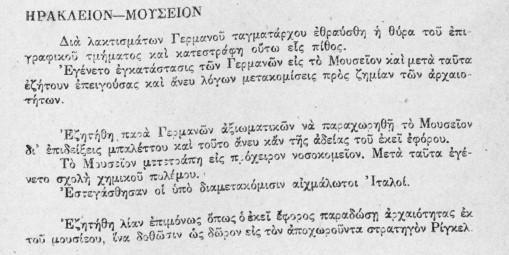

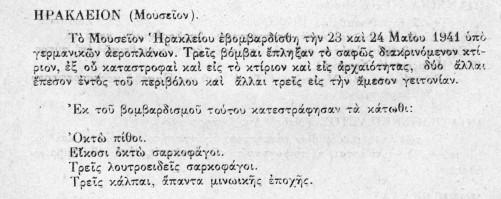

1941

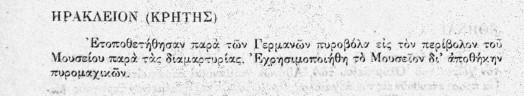

On 23 and 24 May 1941, German aircraft bombed the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. The bombs hit the building, causing extensive damage. Most of the antiquities were unharmed because they had been concealed the previous year, as other major Greek museums had done at the same time to protect the antiquities. The Museum building was requisitioned by the occupying forces and artillery was placed in the garden. The Museum was used as a munitions store, a school of chemical warfare, a field hospital and, in 1943, a prison camp for Italian prisoners of war.

The final damage to the Museum was caused on 9 February 1944, when the area was bombed by Allied aircraft shortly before the German withdrawal, and lastly on 2 June 1945, when a ship full of munitions blew up in the harbour.

1949

Work was resumed on the reorganisation of the Museum, which had been interrupted by the War.

The Heraklion Tourism Committee contributed to the improvement of the appearance of the Museum and the layout of the garden, with the help of Androcles Xanthoudides, the Inspector of Agriculture of Crete.

1950

The unpacking and recording of the antiquities which had been stored in crates during the Second World War continued. Work began on repairing the damage caused to the building, the display cases and the antiquities by the War and the lengthy storage of the last. The numerous visitors to the Museum in the autumn of 1950 were able to visit the first four reopened rooms.

1951

The reorganisation continued with Marshall Plan funding: work was completed on the seven ground-floor rooms and new metal display cases were ordered from London. These cases remained in use until 2006, when the Museum closed for the most recent refurbishment of the building and re-exhibition of the collections.

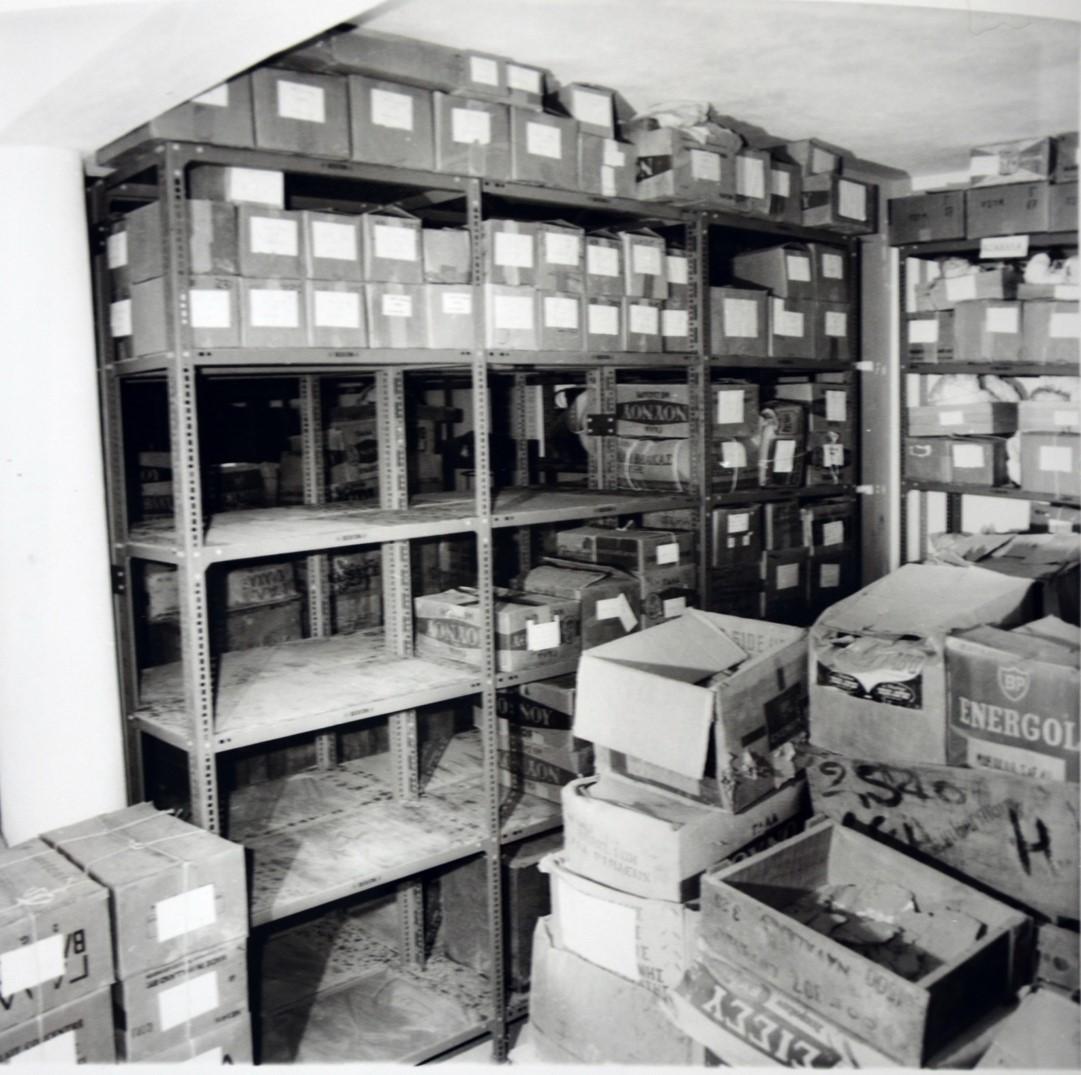

1953

Spacious underground storerooms were constructed for the antiquities not on display, while building work continued on the new wing.

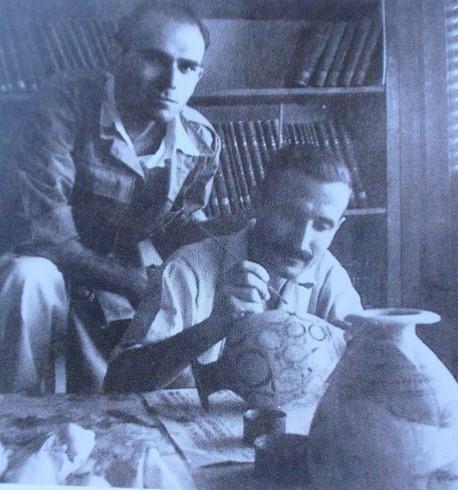

The Scientific Collection was exhibited in the old, repaired display cases of the first Museum. It soon attracted international scholars of the Cretan past. In the conservation laboratories, the work of restoring antiquities continued apace, undertaken by artists Thomas Fanourakis and Ioannis Migadis, chief technician Zacharias Kanakis, and his assistant Ioannis Meramvelliotakis.

1955

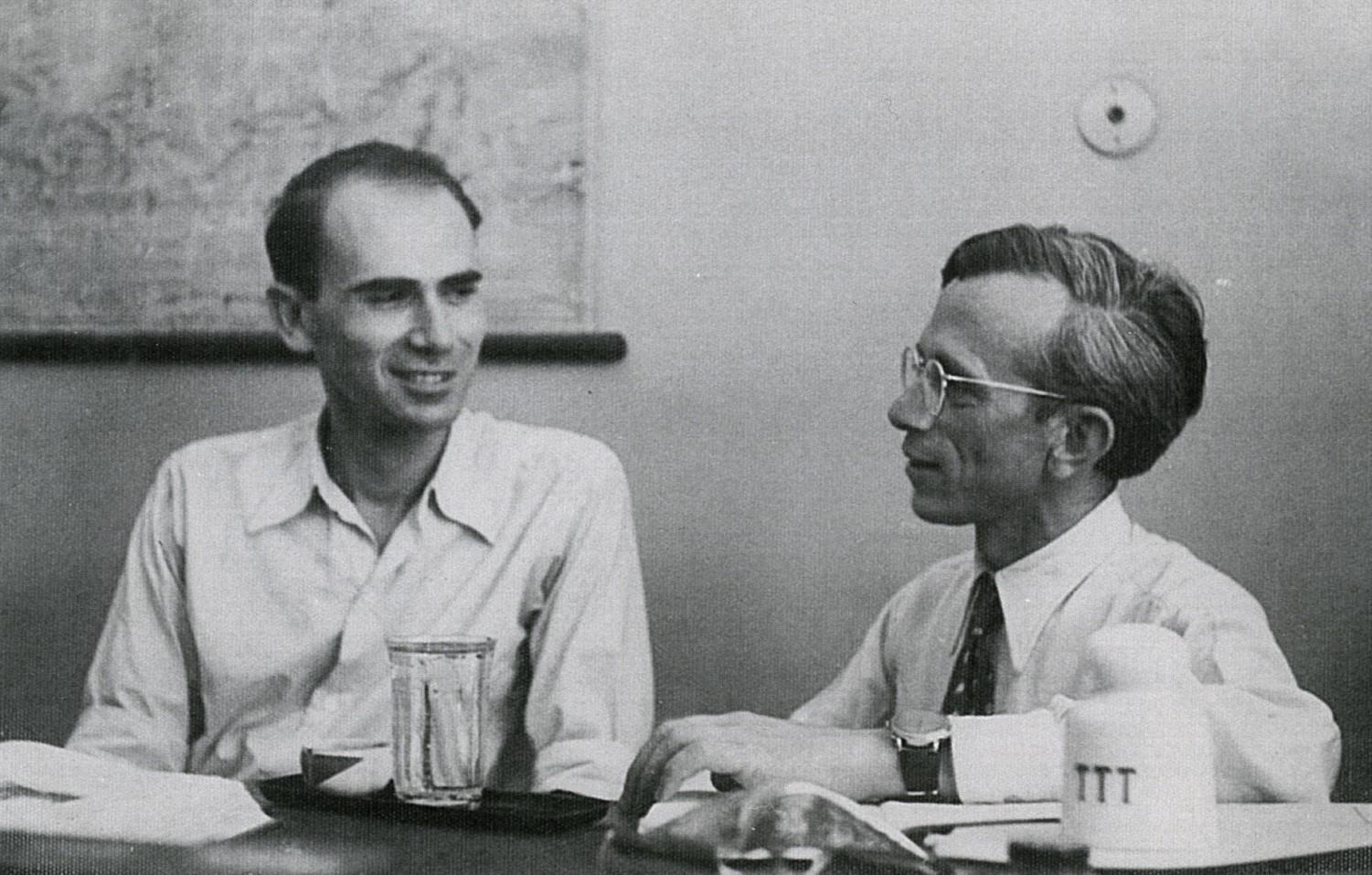

After the War, the Heraklion Museum doubled in contents and size. The partnership between Director Nikolaos Platon and Curator Stylianos Alexiou led to the revival of the Museum and its promotion as a hub of scientific excellence, similarly to the earlier collaboration between Hatzidakis and Xanthoudides.

1956

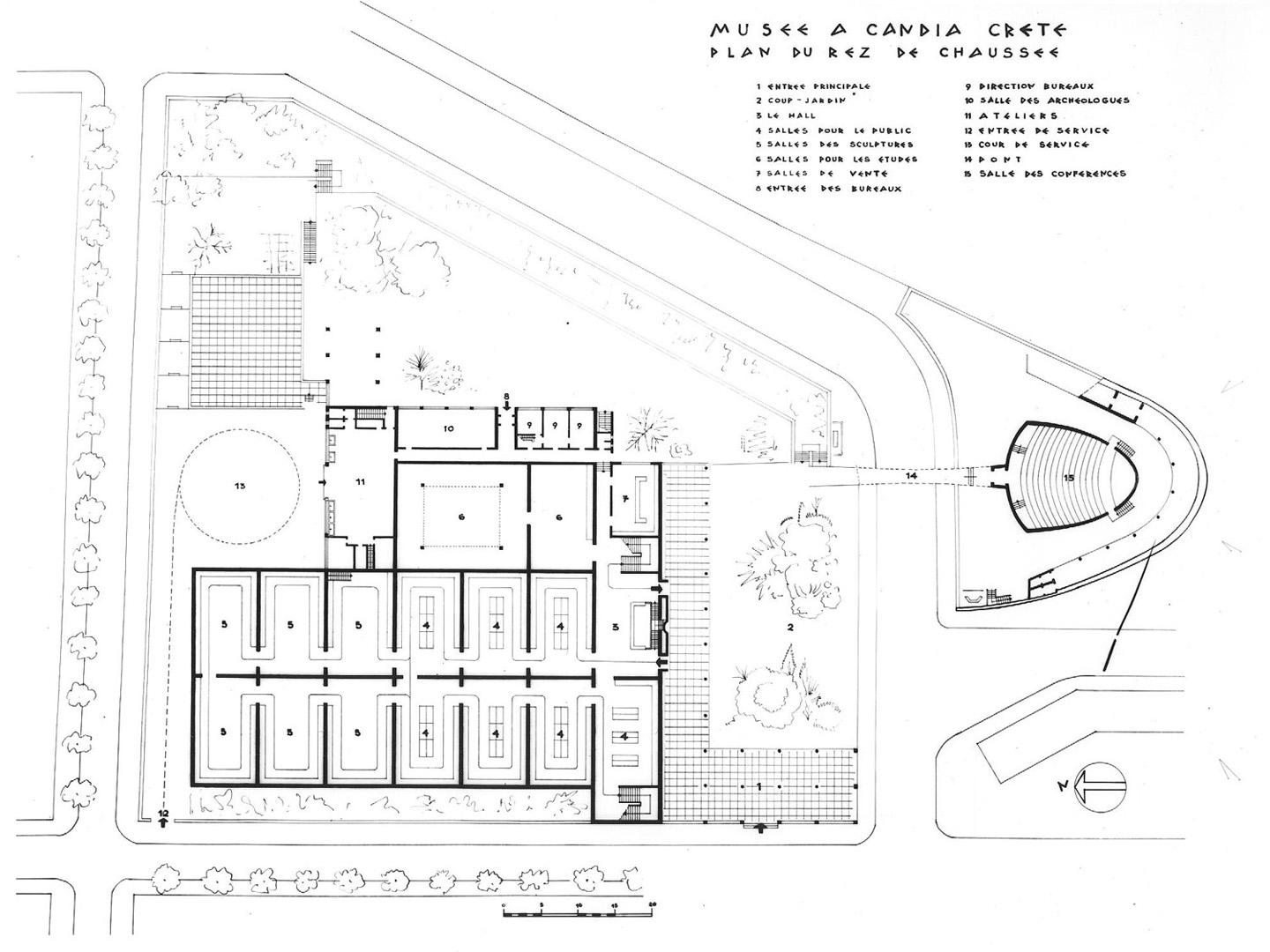

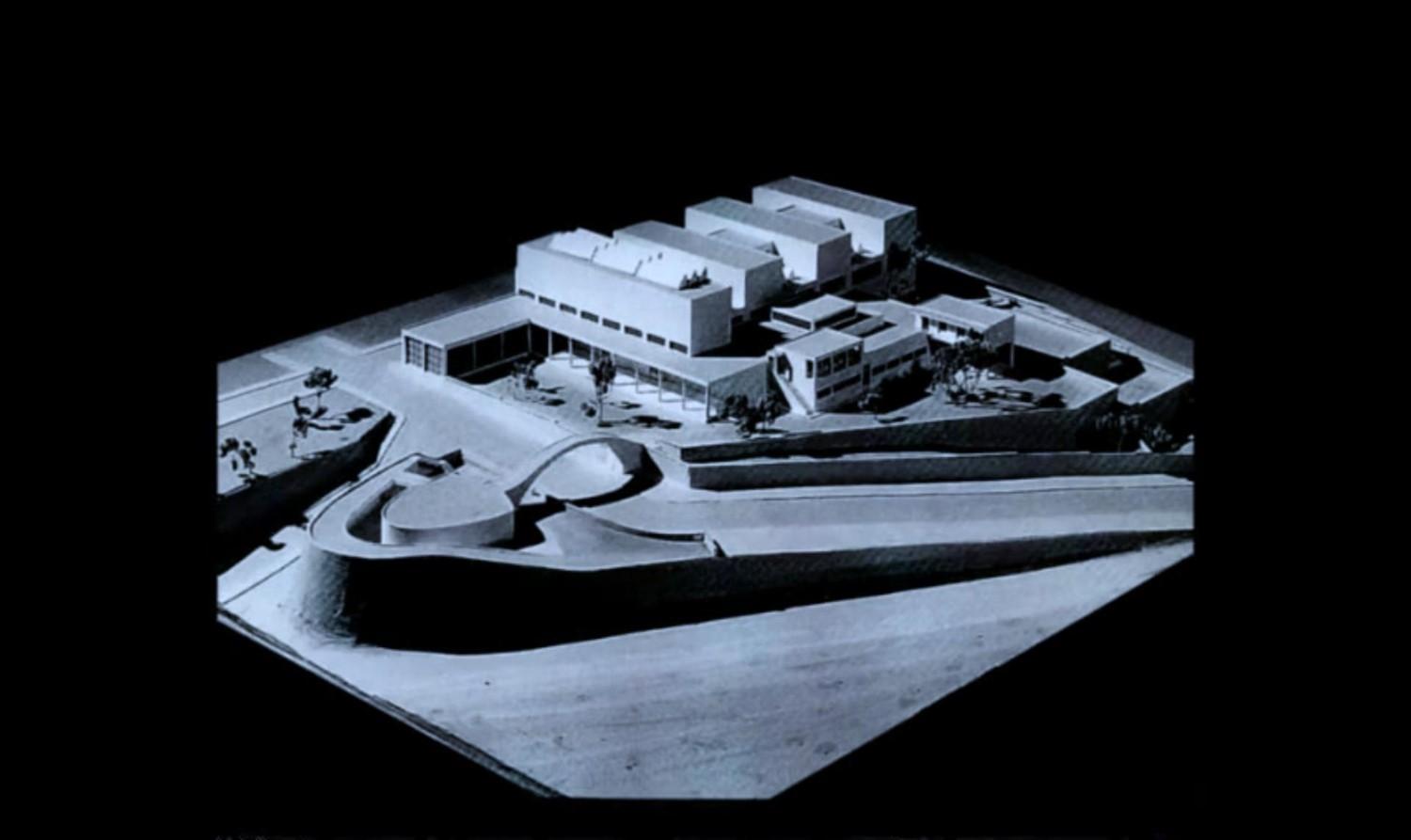

The Stoa housing the Epigraphic Collection was constructed on the Alcazar Bastion. Karantinos’s original plans, including a lecture amphitheatre and an aerial bridge connecting the building to the Museum garden, were never implemented.

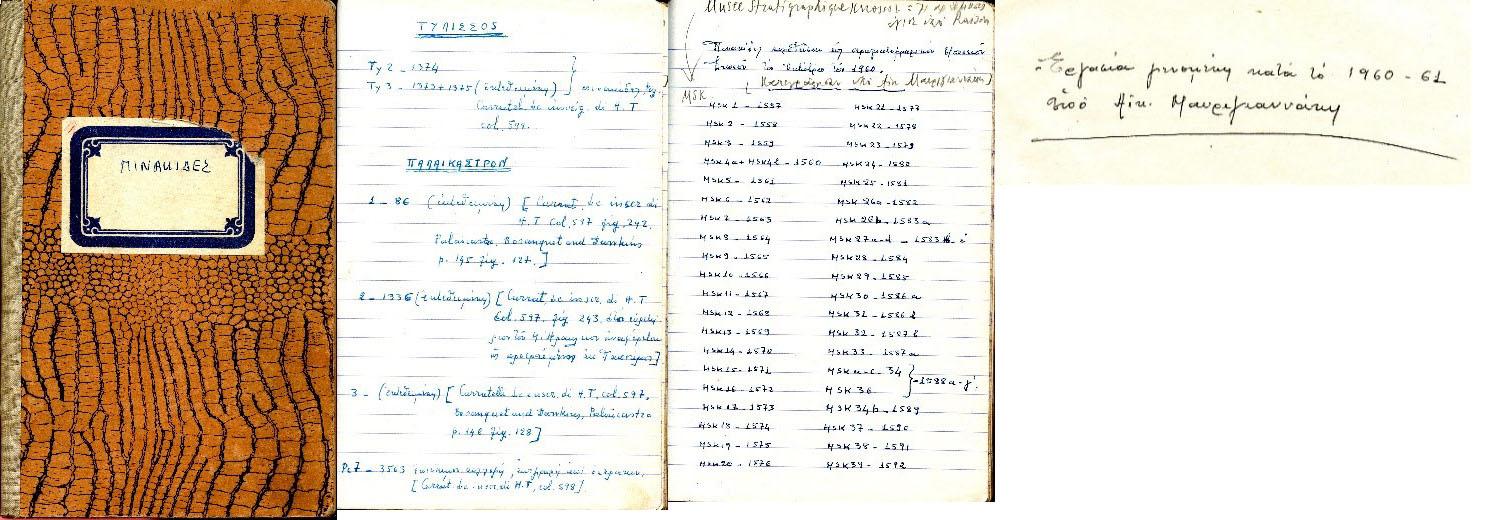

1959

After approximately 20 years, the north wing of the Museum was completed, comprising eight galleries and four basement storerooms. Artificial interior lighting was also installed in all the rooms, as the exhibition had hitherto depended mainly on natural lighting. New foreign-language illustrated guidebooks were published. The storerooms were organised, the numismatic collection was arranged by archaeologist Anastasia Logiadou-Platonos, and the Linear A and B tablets were arranged in special cabinets by archaeologist Aikaterini Mavrigiannaki.

1960

The area surrounding the Museum was laid out with a railing, a pavement and 100 ornamental trees and shrubs, becoming a landmark of the city. New display cases were ordered for the Scientific Collection, which was carefully set up and remained a focus of attention.

1961

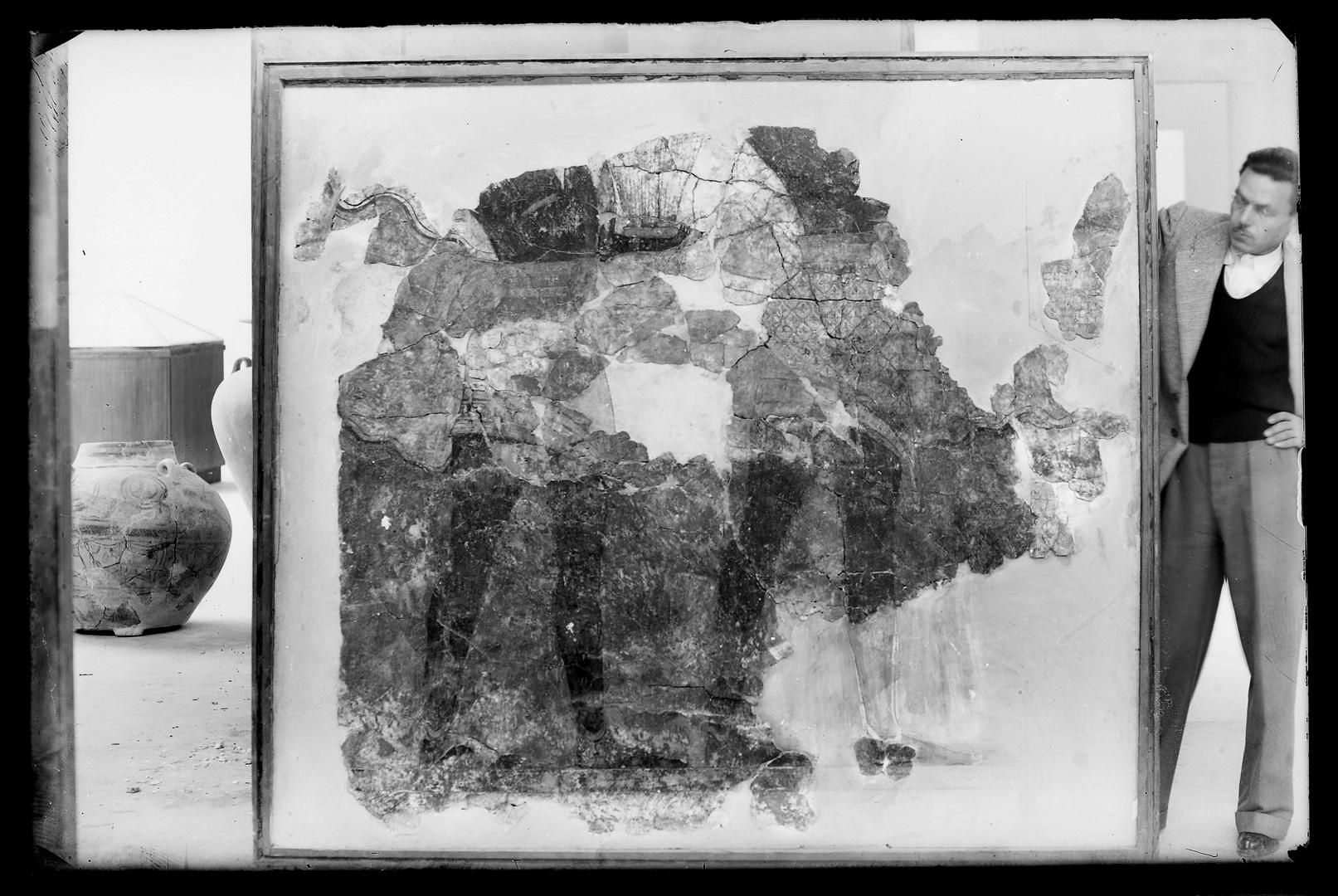

In the early 1960s, during the period of the “Greek economic miracle”, the Heraklion Museum remained extremely active. The infrastructure and landscaping work continued, with the construction of a separate storeroom for materials and the laying of a pavement in front of the storerooms. The frescoes were displayed in rooms on the upper floor, where most of them can still be seen today. The intensive conservation and restoration of the ever-increasing number of antiquities also continued, carried out by the artists, conservators and technicians working for or with the Museum at the time. The sarcophagi and pithoi shattered in the war were mended. The storerooms were put in order, antiquities were recorded, the photographic archive was organised and the library was rearranged.

1962

The collection of Heraklion doctor Stylianos Giamalakis was purchased by the Greek State on behalf of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. The 4,237 objects were unpacked, conserved, recorded and displayed in a special room on the upper floor which opened to the public in the summer of 1963. The collection was dismantled in the 2000s, while part of it is now on display in the permanent exhibition, in the same room as the Metaxas Collection.

1965

For the first time following the completion of the new building, the Heraklion Archaeological Museum exhibition, under the directorship of Stylianos Alexiou, now filled twenty rooms. New finds from recent excavations were added, while there were also major rearrangements, many of which became permanent, such as the exhibition of the finds from the palaces of Knossos and Phaistos in separate rooms.

The exhibition functioned like a living organism, constantly enriched by new excavation finds and older finds displayed for the first time. Architectural models and plans were also created, in order for visitors to better understand the finds.

1976

Large-scale repairs and waterproofing work were carried out on the Museum roof and skylights.

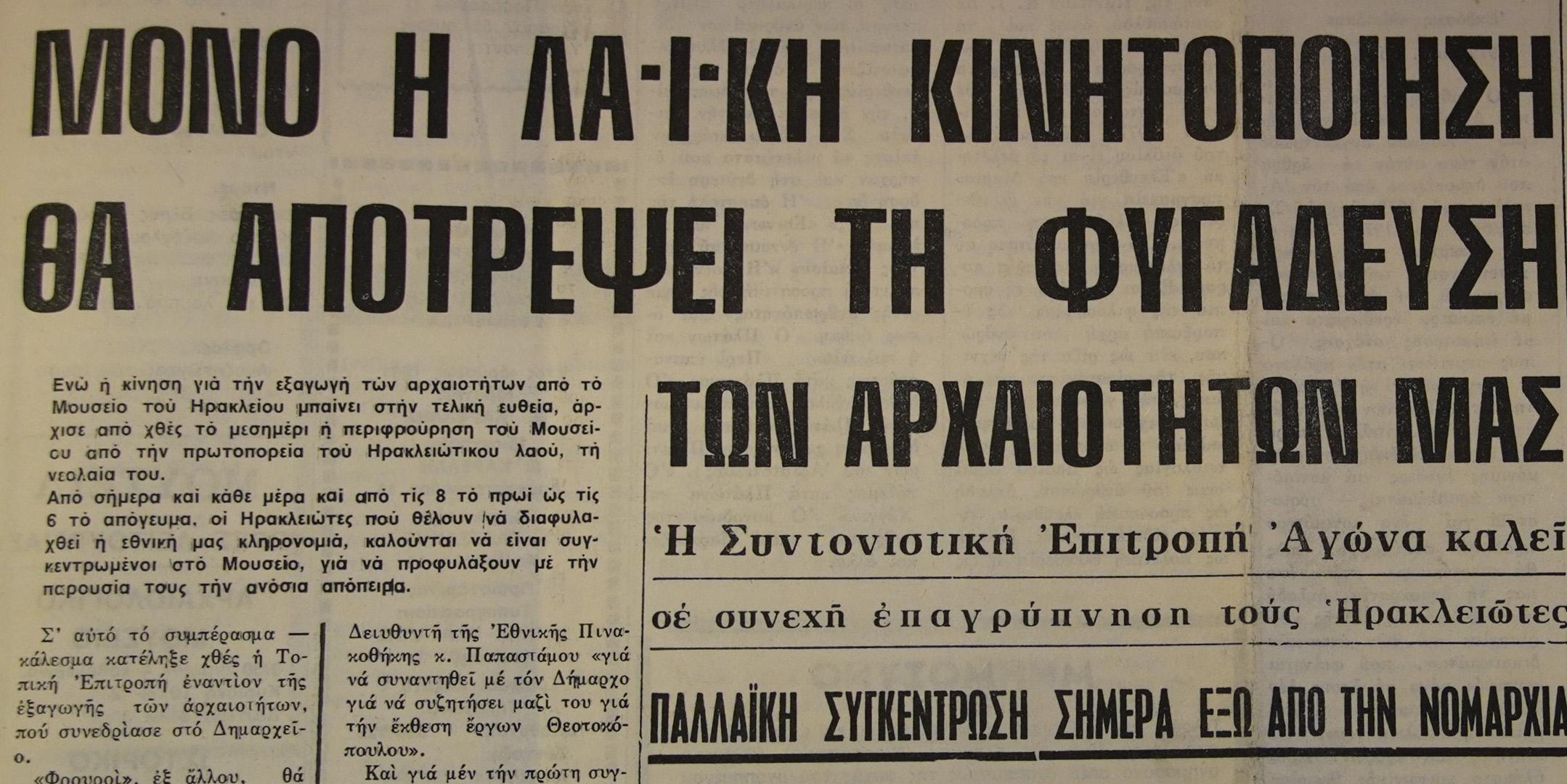

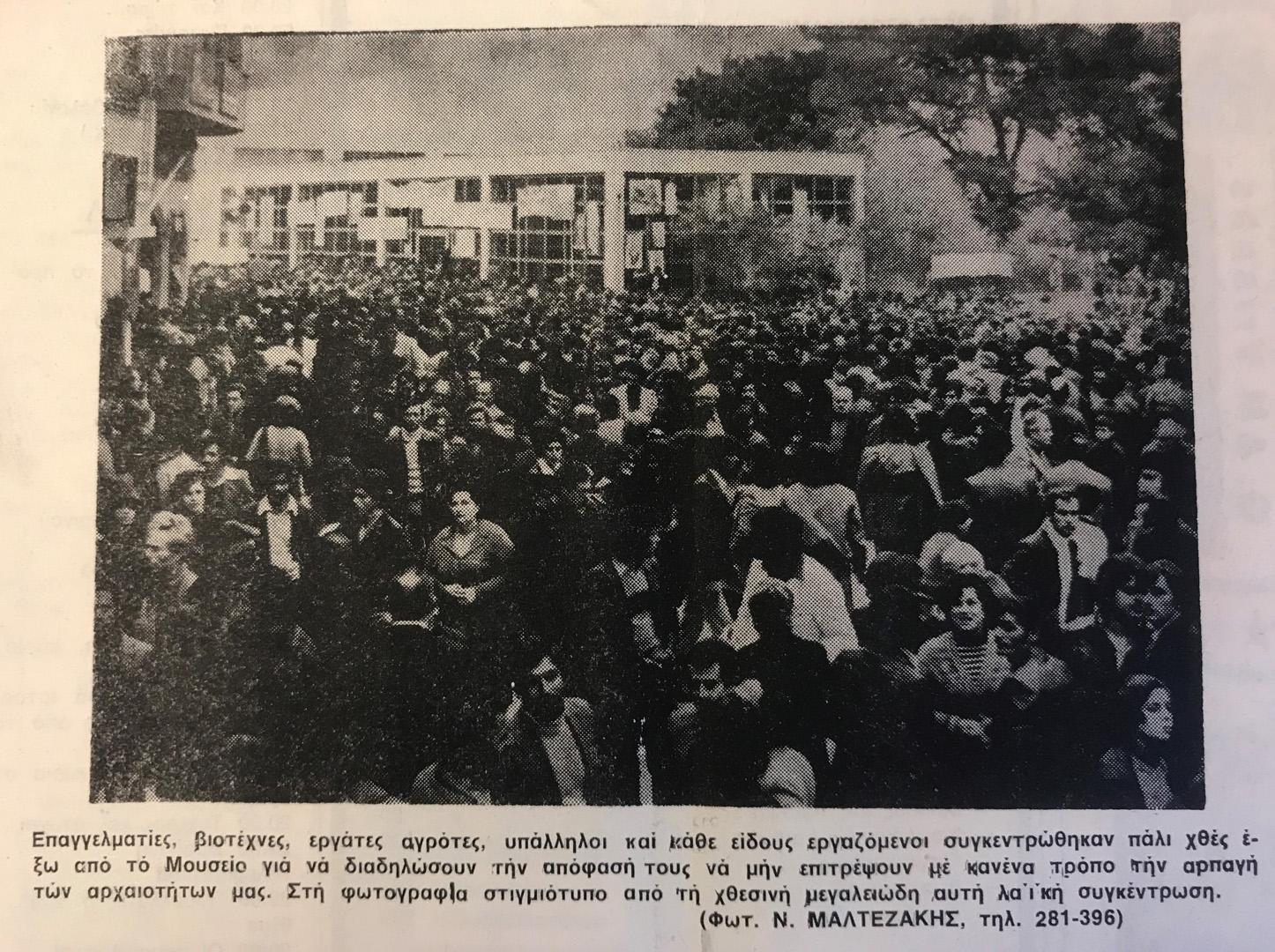

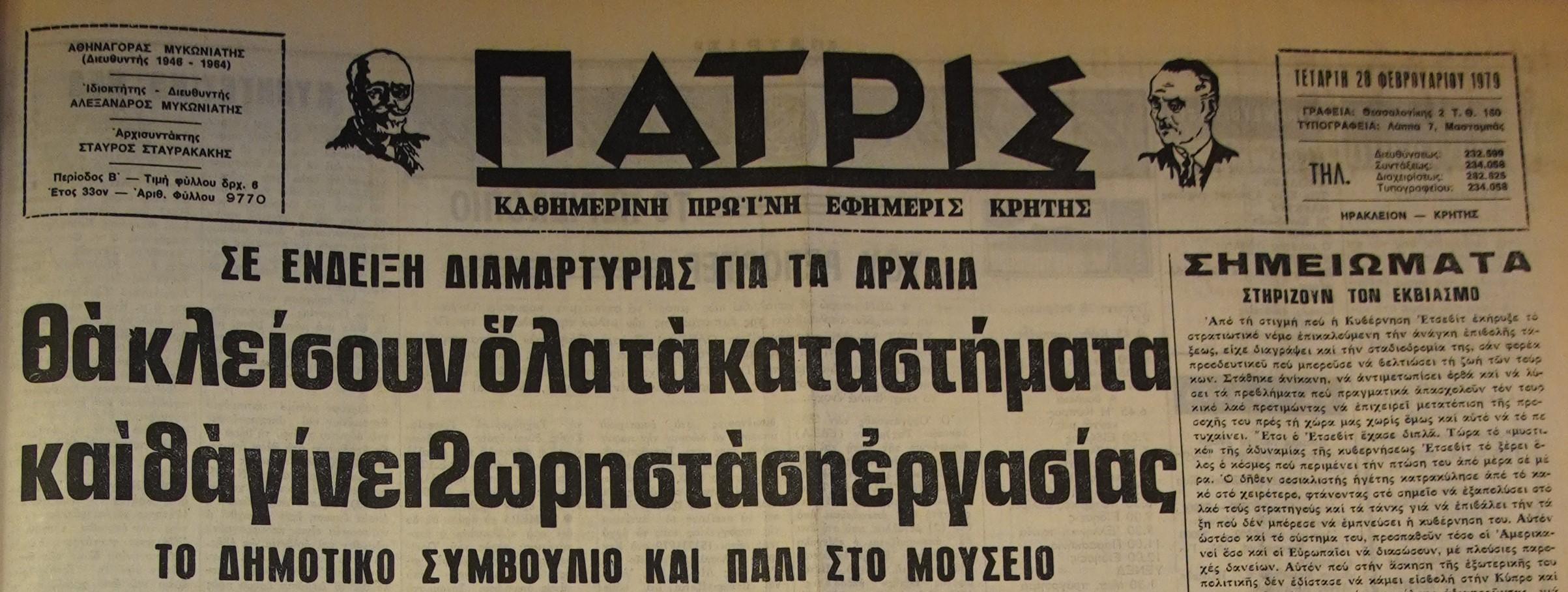

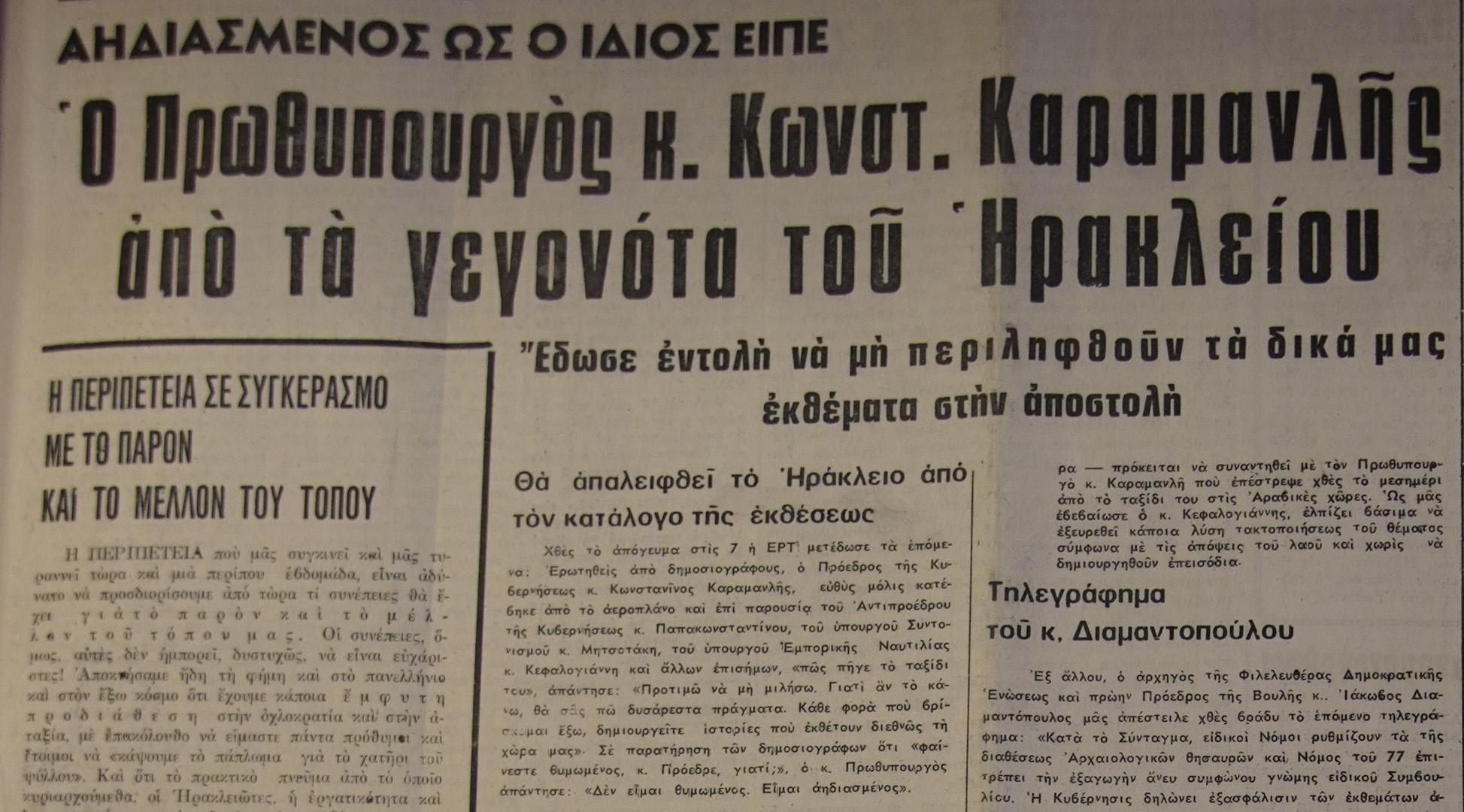

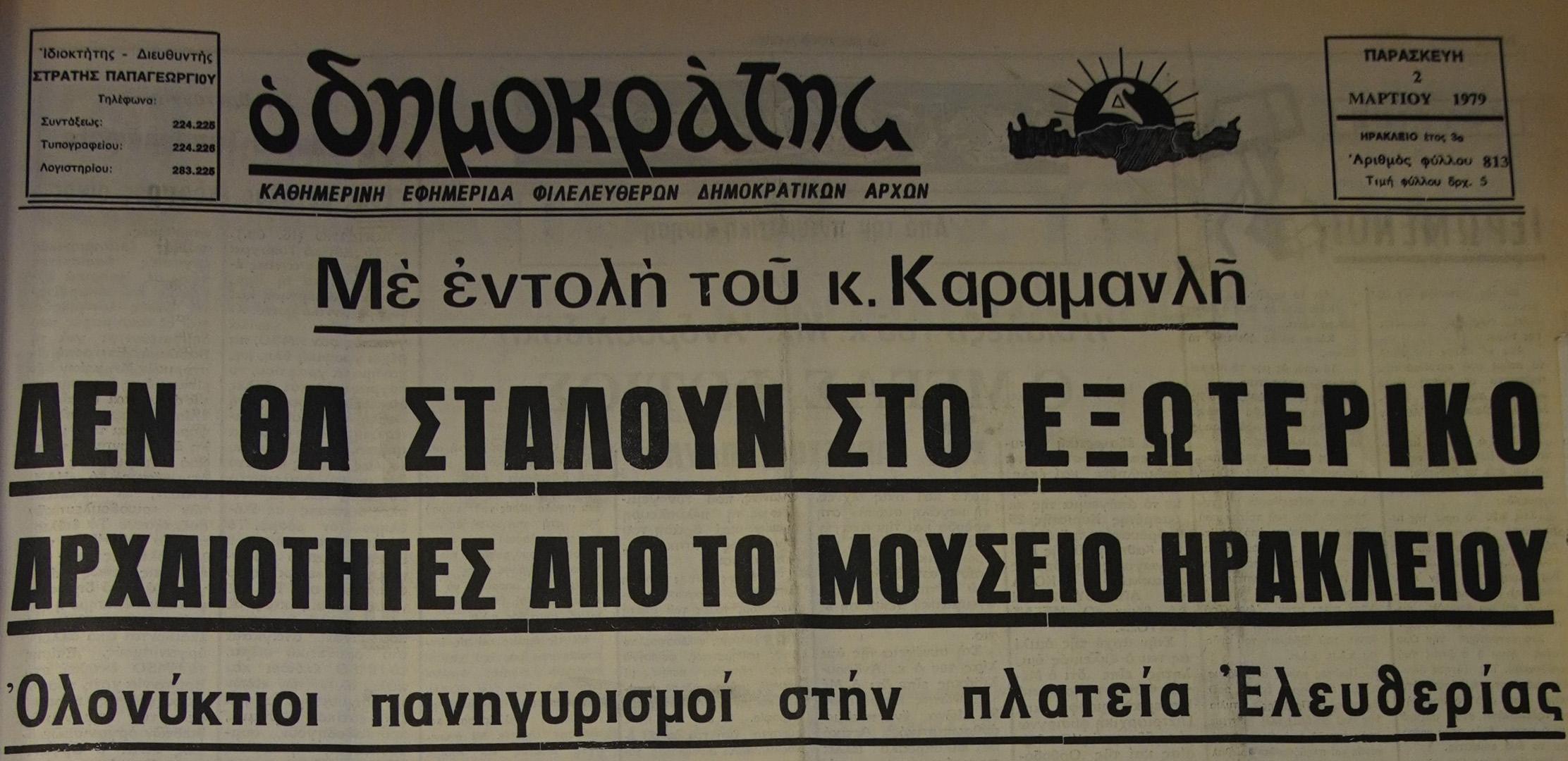

1979

In March 1979, the Heraklion Museum was at the heart of one of the first expressions of the political culture following the restoration of democracy. The citizens of Heraklion protested en masse against lending antiquities from the Museum to the “Greek Art of the Aegean Islands” exhibition to be held at the Louvre and the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Barricades, a strike, calls to the school student community, a “Struggle Coordinating Committee” and tens of thousands of people forced the right-wing Karamanlis government to backtrack. The government was defeated by the Socialist PASOK party in the 1981 parliamentary elections two years later.

1980

In the 1980s the Heraklion Archaeological Museum was marked by the directorship of Yannis Sakellarakis. Besides his excavation and writing activity, he also contributed to the new layout of the storerooms and the Scientific Collection, which radically changed form.

1987

In the late 1980s, maintenance and renovation work was carried out on the Museum buildings. Alongside the ever-increasing work of the Ephorate of Antiquities, Museum Director Charalambos Kritzas ensured that the technical infrastructure was modernised and security systems were installed. The library was moved to a new room and the photographic archive was organised, thirty years after its postwar classification.

1993

Following coordinated efforts and negotiations, the Heraklion Museum acquired the plot just 6 m. north of it, belonging to the Kalokerinos Foundation, via the Finance Ministry exchange process.

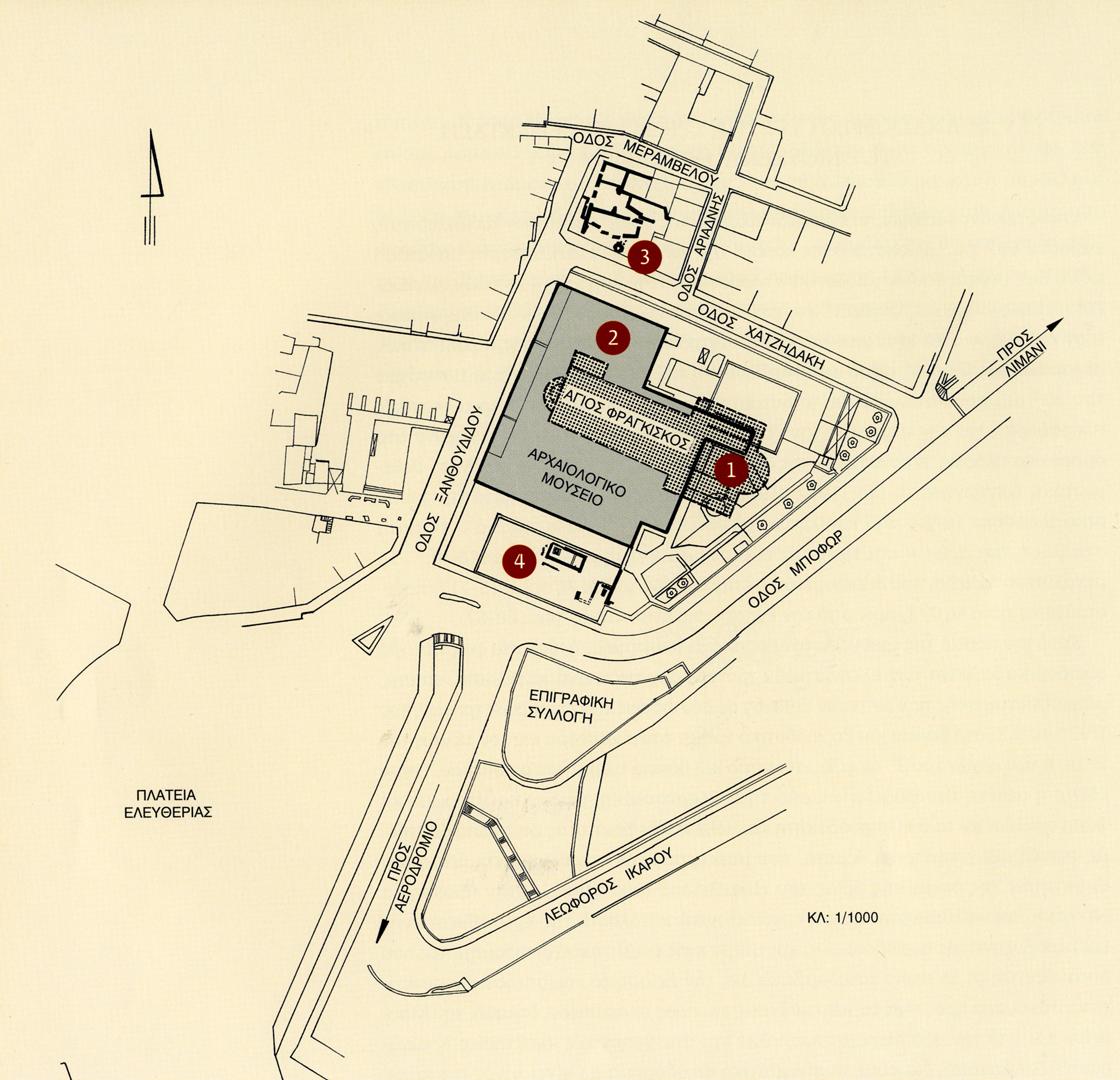

- The Venetian Friary of St Francis

- The Heraklion Archaeological Museum

- The plot north of the Museum, intended for the administrative offices.

Plan by S. Spinthakis 1997, in Ioannidou-Karetsou A., Markoulaki S., Poulou-Papadimitriou N. and Penna V. 2008. Heraklion. The Unknown History of the Ancient City. Nea Kriti Editions, Heraklion, p. 76 [in Greek]

1994

The extensive modernisation of the mechanical installations of the Museum, such as the air-conditioning and fire safety systems, necessitated the removal and rearrangement of exhibition display cases, the Scientific Collection and the storerooms. Alterations were also carried out to the building itself, with the addition of false ceilings and machinery on the roof. The prospect of a full re-exhibition was beginning to emerge.

1996

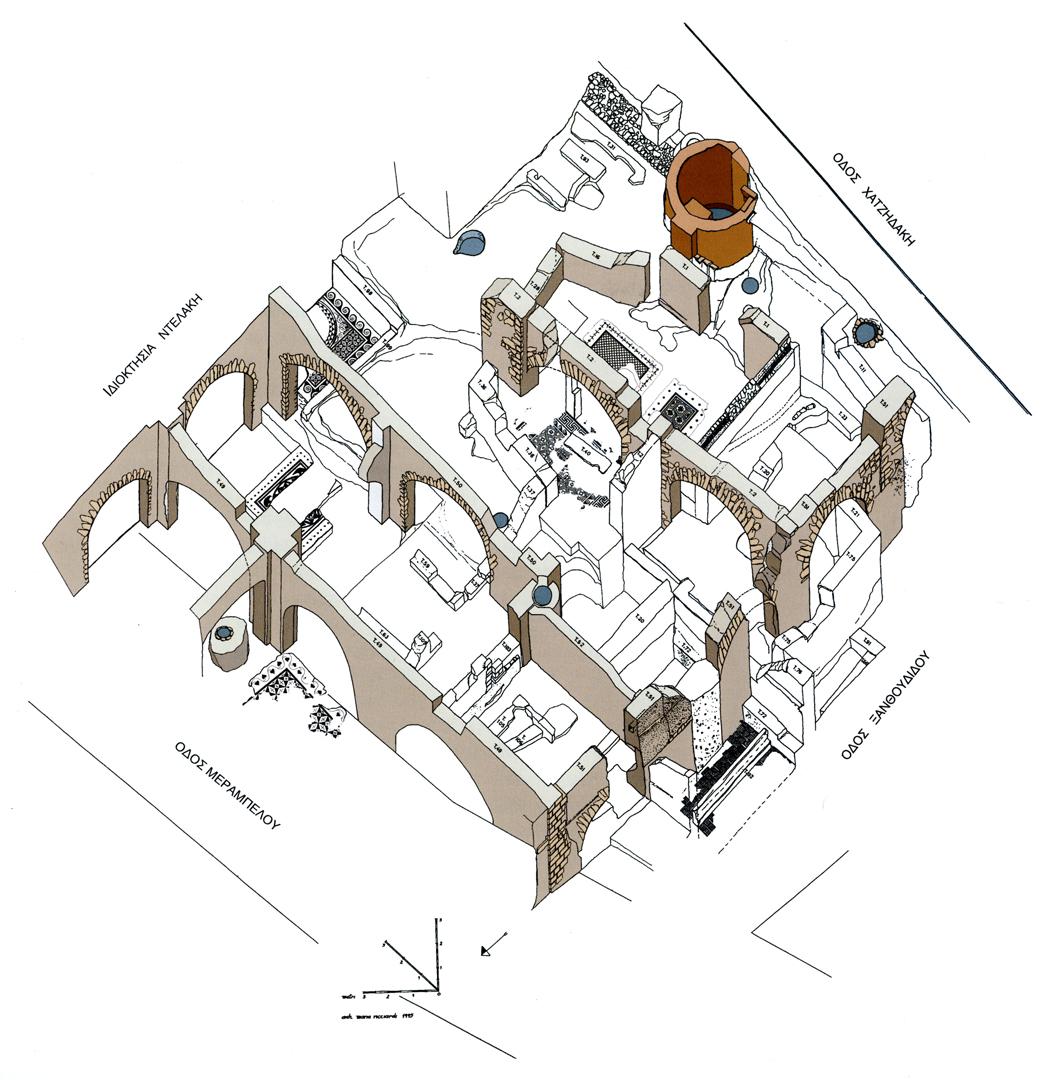

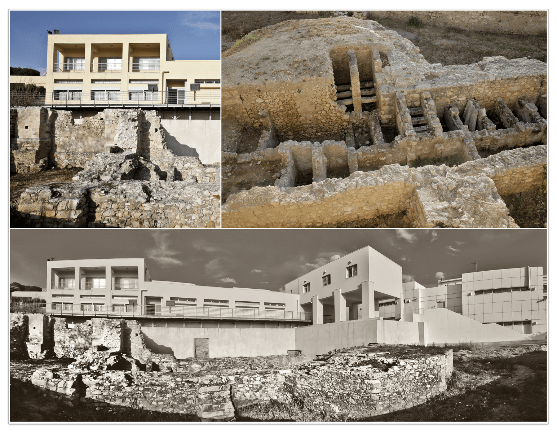

The excavation of the plot was completed under Alexandra Karetsou’s directorship. It revealed complex remains of successive phases, including an Ottoman tekke (dervish lodge), Venetian wells and a Roman villa, which were preserved under an elevated entranceway. The three-storey building now housing the administrative offices of the Museum and the Heraklion Ephorate of Antiquities was built on the site a few years later.

1997

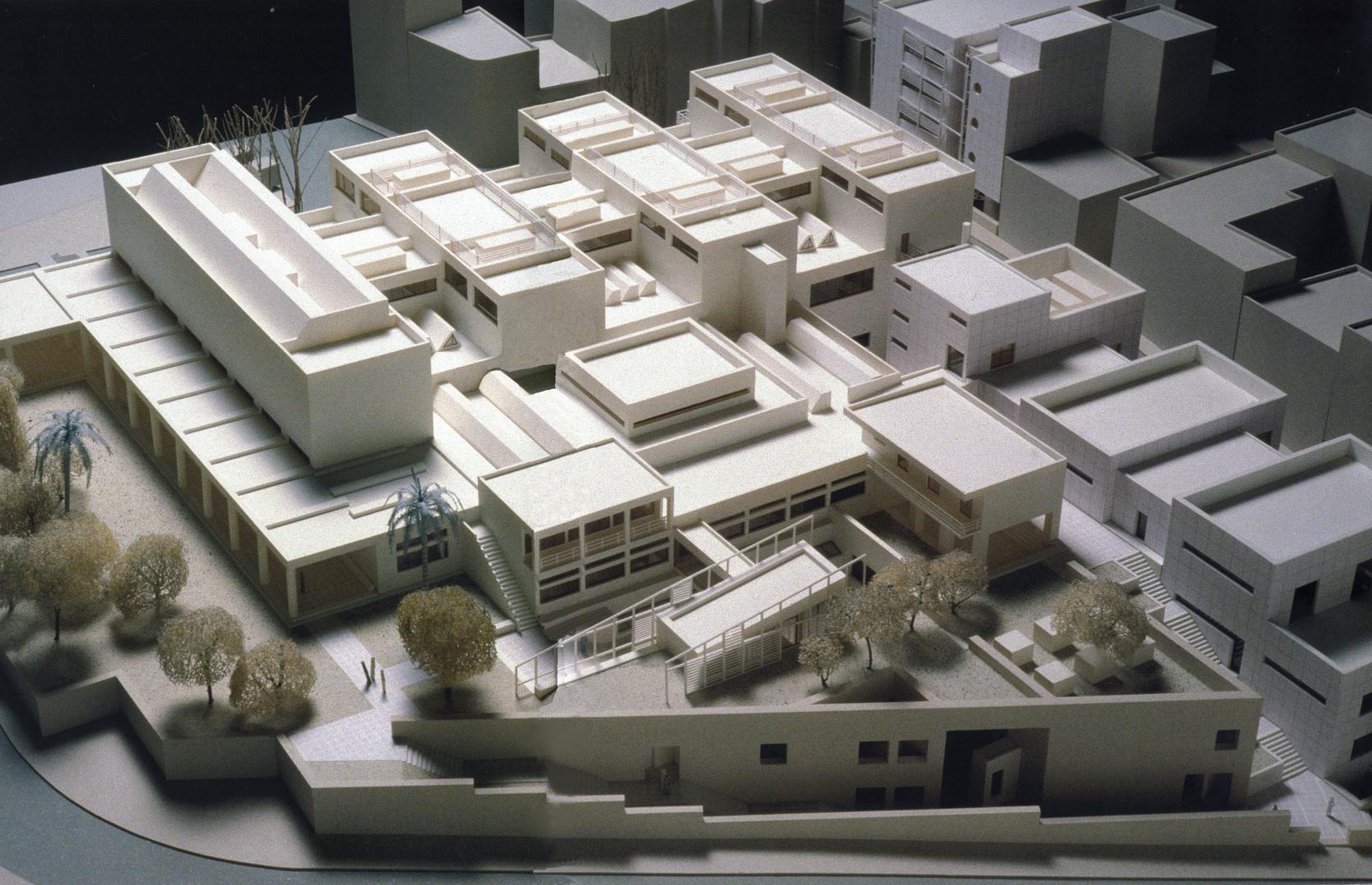

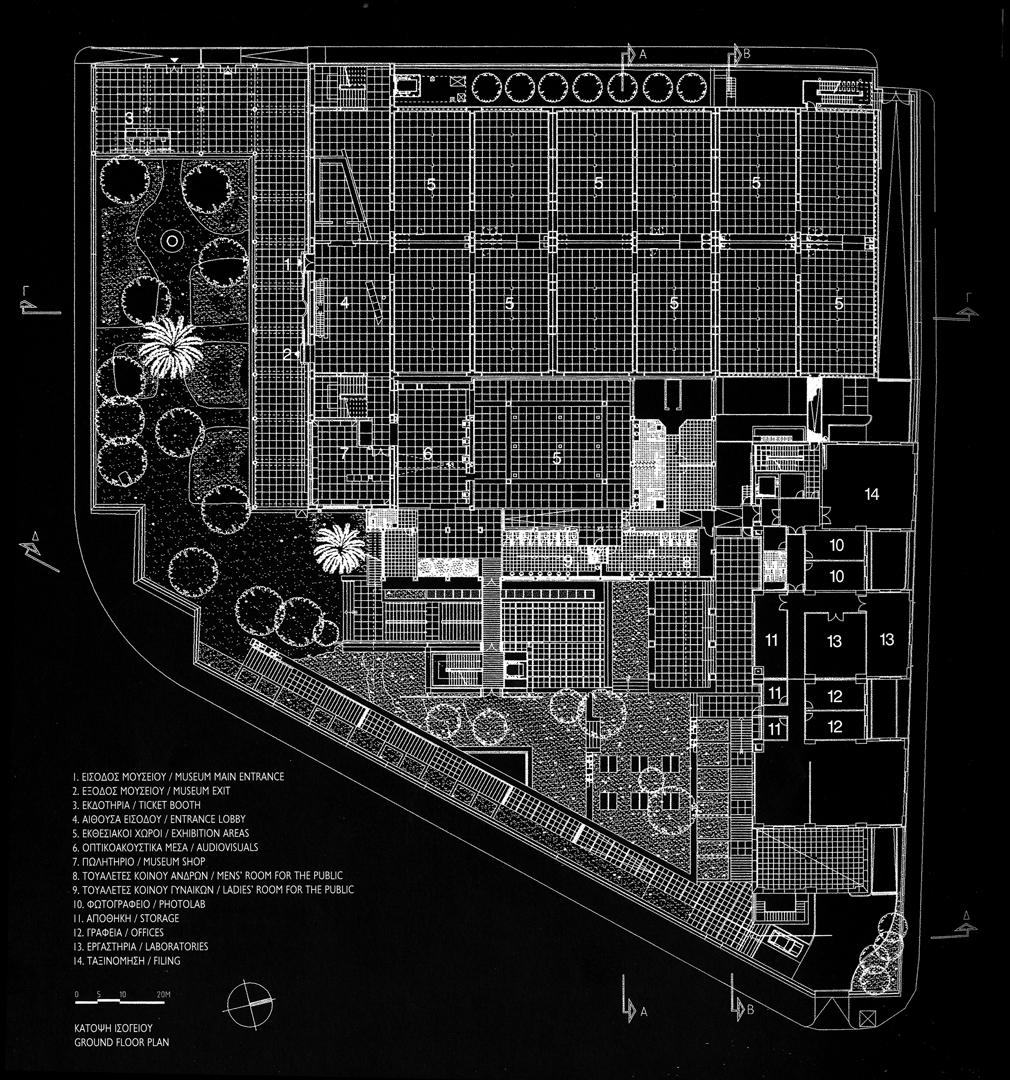

Nearly 60 years after its construction, the Heraklion Archaeological Museum was in need of a radical refurbishment. The wear to the building materials and the load-bearing structures could no longer be managed by temporary measures. The A. Tombazis architectural firm won the tender to draw up a study. The main concern, alongside with the modernisation of the Museum and the addition of extra rooms, was the preservation and restoration of the shell of Karantinos’s building, as a monument of the international Modernist movement.

Nikolaos and Theano Metaxa donated their collection to the Greek State. Most of it was donated to the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, while part of it, according to the donors’ wishes, is displayed in the Malevisi Archaeological Collection in Gazi

2002

The Extension and Modernisation of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum Project was launched with EU funding. The project included the restoration of natural lighting, new electromechanical installations, a new wing of storerooms and laboratories, and a new administrative building. The first sub-project to be implemented was the packing and transfer of the antiquities kept in the storerooms.

2004

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum was separated from the Ephorate of Antiquities and began to operate as an autonomous Directorate under Director Nota Dimopoulou-Rethemiotaki, and subsequently as a Special Regional Service.

2006

While work was being carried out on the Permanent Exhibition, a small-scale Temporary Exhibition was set up, with 400 of the most important and popular exhibits of the Museum. The aim was to fill the gap caused in the economic and cultural life of the city by the closing of the Museum for the first time since the 1930s.

2007

The postwar exhibition of antiquities at the Heraklion Museum, the work of Ephors Nikolaos Platon and Stylianos Alexiou, was dismantled for the first time in order for the building work to begin, together with the conservation of thousands of exhibits.

2010

Work on the Museum re-exhibition continued under Athanasia Kanta, followed by Giorgos Rethemiotakis, under whom it was completed a few years later.

The surrounding area, the historical Museum garden, was also landscaped with funding from the “South Aegean-Crete” EU Regional Operational Programme.

The remains of the church of St Francis, with which the history of the Museum is inescapably linked, were revealed and highlighted.

2012

The gradual reopening of the new exhibition of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum began in August 2012 with the Archaic and Greco-Roman Sculpture galleries. The Hall of Frescoes on the upper floor was opened to the public at the end of the year. Assemblages of the Early Greek and Greco-Roman periods were re-exhibited the following year, together with the Giamalakis and Metaxas Collections.

2014

On 5 May 2014 the re-exhibition of the prehistoric antiquities on the ground floor was completed, forming the nucleus of the Museum’s iconic objects. The new Permanent Exhibition of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum extends across 26 rooms on the ground and upper floor. The official inauguration ceremony was held on 26 June 2014.

On 1 September 2014, archaeologist Stella Mandalaki took over as Director of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.